World Geostrategic Insights interview with Hugh Pope on Turkish public perception of the West, views on democracy in the Middle East, and random selection as a better way of democratic governance than our current system of elected representatives.

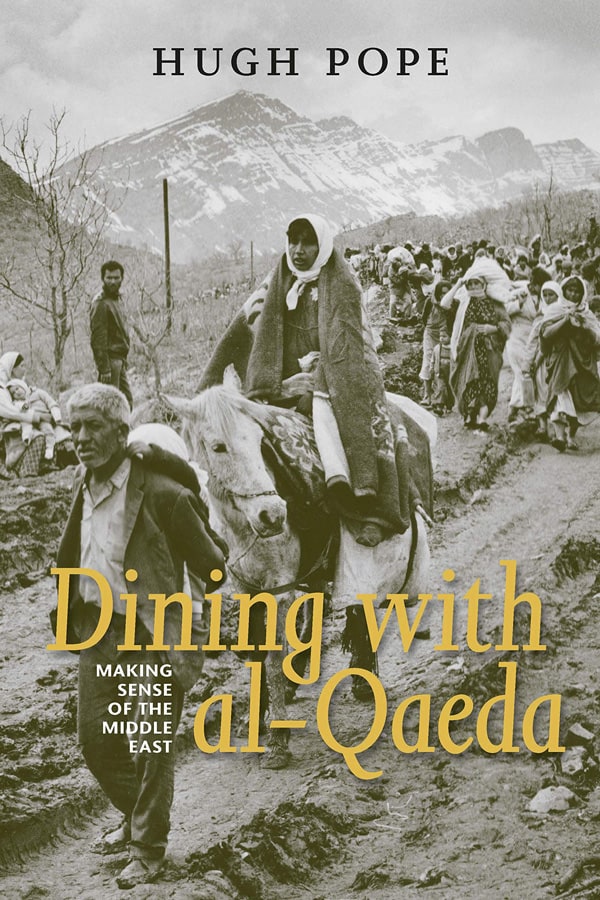

Hugh Pope is a writer, author of “Dining with al-Qaeda: Making Sense of the Middle East”; “Sons of the Conquerors“ and co-author of “Turkey Unveiled“. Now co-editing his late father Maurice Pope’s The Keys to Democracy: Sortition and a New Model for Citizen Power.

Hugh Pope is a writer, author of “Dining with al-Qaeda: Making Sense of the Middle East”; “Sons of the Conquerors“ and co-author of “Turkey Unveiled“. Now co-editing his late father Maurice Pope’s The Keys to Democracy: Sortition and a New Model for Citizen Power.

Q1 – Russia and China appear to have surpassed the United States and the European Union in winning the sympathy of ordinary Turks. Anti-Western sentiments have gained momentum not only among Erdoğan’s AKP voters, but also in the base of opposition parties. Anti-Western narratives have dominated the public debate and that there is no significant political actor, ideological or social group that seems to be pushing to defend Turkey’s traditional Western vocation. It is also rare to see public support for a Western perspective in Turkey’s foreign policy. Western skepticism also emerges in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, where the majority of Turks believe that the U.S. and NATO are responsible. You lived in Turkey for many years as a correspondent and are also the author of “Sons of the Conquerors: The Rise of the Turkic World”, and co-author of “Turkey Unveiled: A History of Modern Turkey”. How do you explain the surge of anti-Western in Turkey? Is it a transitory perception or has it taken deep roots? Does political and cultural cooperation with the West still have possibilities for development?

A1 – The short answer is that I believe the rise in anti-Western attitudes in Turkey, especially as reported in the West, is indeed a transitory perception. If Turkey should suddenly need the West’s help and get it, as in the 1950s or the late 1990s/early 2000s, that attitude could reverse quickly.

The longer answer would have to take into account the basic dynamics of Turkish history. Turkey has always had to hedge its bets. The Republic of Turkey, which celebrates its centenary next year, was founded after a decade or more of bitter, exhausting war with what are now known as ‘Western’ powers. At the same time, the founding ideology of the republic – a positivist secularism – was very much in imitation of that same “West”. There were similar swings relating to the U.S. in the Cold War: Turkey became pro-U.S. when Russia threatened, anti-U.S. when Washington punished Turkey for its position on Cyprus.

The national mood is also affected by Turkey’s current leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who has made it his trademark to exaggerate national fears about foreign meddling and intransigence, particularly in relation with the West, as a way to stoke up domestic support. Western actions on refugees and its policies on numerous Middle Eastern topics affecting Turkey – the meltdown in Syria in which the U.S. now backs avowed foes of Ankara, the unjustified 2003 assault on neighbouring Iraq, and the West’s general favouring of Israel against fellow-Muslim Palestinians – have given anti-Western Turkish politicians ample material to work with.

With nine sometimes difficult land and sea neighbors to worry about, and a position on the fault-line of Asia and Europe, it’s not surprising that Turkey often has to balance its policies warily. Nevertheless, it is a mistake to box up all Turkey’s foreign preferences in the person of a leader like Erdoğan and his domestic agenda. There remains a strong constituency in Turkey that favors being closer to the richer and more powerful West, and the West should never neglect that.

Q2 – According a survey of the Arab Barometer network, conducted across nine countries and the Palestinian territories for BBC News Arabic, between late 2021 and Spring 2022, there has been a regional shift in views on democracy since the last survey in 2018/19. There’s a growing perception that democracy is not a perfect form of government, it won’t fix everything, and that the economy is weak under a democratic system. In 2011, the Arab Spring captured imaginations around the world for the call for democratic change. Was it only imagination? Is democracy stalling in the Middle East as the Chinese model advances? Or simply, can the model of democracy we conceive in the West not be applied to Middle Eastern society?

A2 – If pollsters found a sense of public frustration in the Middle East with the idea of electoral democracy, it is perhaps not surprising. Monarchies there make little pretense of democratic representation, notably in the Gulf, yet they find great favor with Western powers; countries which in a previous generation of uprisings in the 1950s and 1960s overthrew monarchies in Egypt, Libya or Syria are now in a barely governed mess, don’t have meaningful elections or enjoy any real public representation; then there are countries like Iran and Turkey that say that just because they have technically clean elections, they are democratic – no matter how unfair or unrepresentative the electoral process may be.

It’s not clear to me either that a desire for electoral democracy, say, is the most useful lens to view what is called the Arab Spring. It seems to me that the movement was more of an uprising for more freedoms in the face of oppressive, unjust rule and a popular perception of weakness in the authoritarian, ex-military leaders that usually ran their affairs. The Middle Eastern ‘street’ is very sensitive to changes in the balance of power, and it picked up a sense that the US under President Barack Obama would no longer give unquestioned backing to pro-US tyrants. But the US didn’t back the revolutionaries, who were not that numerous as a percentage of the population. In the end, tragically for the often young, idealistic protestors of the uprisings, it turned out that the governments were better organized, better equipped and better able to take advantage of a backlash against domestic disorder.

Q3 – Remaining on the general theme of democracy, you are editing and preparing for posthumous publication your late father Maurice Pope’s last book “The Keys to Democracy: Sortition and a New Model for Citizen Power”. The assumption is that our current system of elected representatives is broken and that there is a better way of governing ourselves, the random selection, that is more transparent, closes the doors to corruption and avoids polarization. Can you explain with more details?

A3 – Thank you for this question! My father was a classicist who was deeply convinced of a couple of points about politics that were taken as self-evident in the ancient Greek world: firstly, that constitutional systems based on popular elections always produce oligarchies; secondly, that democracy, the Greek for people power, meant bringing all adult citizens into decision-making on an equal basis and by lot – much like modern juries. (In those days, this excluded women and slaves, ideas that are of course unthinkable today). Those selected first deliberated on shared problems and then legislated, judged and acted as the executive in the name of the city. This system is also called sortition.

My father also believed that empowering citizens through sortition was the key reason that a city like Athens, whose population would not fit half a modern football stadium at the best of times, produced far more than its fair share of immortal thinkers. They invented many of the basic planks of Western civilisation (tragedy, comedy, schools of philosophy, mathematical theorems and so on).

My father therefore set about writing a book that would demonstrate to a general audience what sortition – bringing representative samples of people into decision-making through selection by lot – would look like today. While the book was rather unique (and couldn’t be published) in the 1980s, much has now changed. Over the past five years, a trickle of books on sortition has turned into a torrent. The Keys to Democracy will be later to the party than it expected, and is now being published by Imprint Academic in Spring 2023.

Many groups have sprung up in recent years to promote aspects of sortition. They share values and principles, but most focus on one country: for example, Sortition Foundation in the UK, Equality by Lot in the US, Mehr Demokratie and its Citizens’ Assembly project in Germany, Tegen Verkiezingen in the Netherlands, G1000 in Belgium, WeDoDemocracy in Denmark, Deliberativa in Spain and newDemocracy in Australia. Paris-based DemocracyNext adds a more international and radical vision: to build new institutions that can put sortition “at the heart of a new democratic system,” not just in government but in the workplace too.

The aim is not to bring the sixth century BC back to life or have a lottery to choose the president or prime minister. The approach builds on a growing wave of Citizens’ Assemblies, which are randomly selected with stratification so that representatives are a true sample or reflection of their communities or countries. In the past decade, more than five hundred such assemblies in dozens of countries have been finding original solutions to problems that have long stumped politicians: climate change in the UK, France and elsewhere; conflict resolution in the Philippines and Bosnia; and in Ireland, breaking the logjam on abortion and same sex marriage.

Hugh Pope – Writer, Advisory Board member at DemocracyNext and former Director of Communications & Outreach at the International Crisis Group.