By David Davidian

The following fictional Red Cell scenario is intended to stimulate alternative thinking and challenge conventional wisdom, tying together events in operational fiction with national realities.

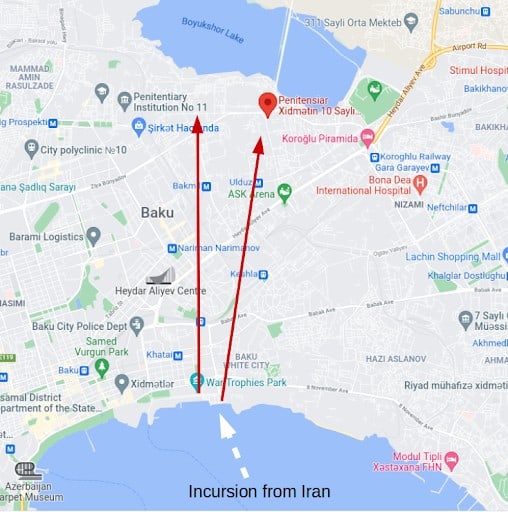

Local Map of the Incursion into Baku from Iran.

Local Map of the Incursion into Baku from Iran.

We had set up for multiple diversions; any of our teams would be sacrificed for the mission’s success. Since the end of the Second Karabakh War, the goal was to free as many Armenian POWs (prisoners of war) held in several places in and around Baku, Azerbaijan. It was a very tough operation considering it was planned in Europe and did not involve the Armenian government. There was limited “kompromat” and money to pay off lower-level Azerbaijani oligarchs and several “third country” security services. Multiple escape routes were planned, with POWs being separated and funneled through third countries. The best intelligence we had was that most of our boys were being held in Penitensiar Xidmətin 10 and 11, near Lake Boyukshor, in Baku. If only a handful of POWs made it out — even one — the operation would be considered a political success. One problem was that only a few of our POWs knew Azerbaijani Turkish, while all of our team members knew enough Turkish and European languages and would pass as a Muslim, or Jew, upon inspection. Another problem was that Armenian diplomacy was unable to take on the task of addressing even one POW having been liberated. Armenian diplomats were well versed in business efforts yet towed the government line in all other cases.

The debate over such an operation took months, with military and intelligence experts from the Armenian diaspora stretching from Manchester, England, to Isfahan, Iran. Internal security was something akin to US Black Operations, with constant surveillance. It was estimated such security cost more than the actual Operation Baku. Several security breaches were planned to gauge the extent of regional counter-intelligence protection of Azerbaijan, which is why all references were associated with support of an ethnic separatist movement in Iran. Since Armenian sovereignty barely extends to its borders, there were never any Armenian threats worthy of alarm; besides, there has never been a critical mass of nationalism expressed in Armenia. Since the breakup of the Soviet Union, Armenian policies were always centered around the mystique of the oligarch, much like Azerbaijan, and to a lesser extent, Georgia. All three of these ethnic groups were among the most corrupt during the final years of the Soviet Union. Since then, all three Southern Caucasus republics have taken seemingly separate paths.

One of our commandos, known by locals in Northern Syrian Kurdistan as Jiko, spent several years with YPG groups. He did his best in trying to defend Syrian Armenians from pro-Turkish forces. Jiko knew some of the Al Nusra Syrian jihadists recruited by Turkish intelligence to fight Armenians in the Second Karabakh War. Jiko had only a tiny window of opportunity during the winter of 2020 to infiltrate Azerbaijan with a handful of fellow jihadist-looking, Arabic and Turkish-speaking Armenians.

The second group of infiltrators included Azerbaijani-speaking Armenians from Tabriz, Iran. This group could easily pass themselves off as Azerbaijani villagers, even in Baku. This was important as they would make their way in an Iranian Ghadir seven-man mini-submarine with a shore target of 8 Noyabr Prospekti. This mini-sub was modified for battery-only operation in a one-way trip. Purchasing such a vessel was easy in cash-strapped Iran, but the full-electric conversion was challenging. The Iranian Revolutionary Guard was recruited in towing this mini-sub as close as possible to Baku’s southern coast. The Guard looked the other way, for by 2021 Iranian forces were massing on the Azerbaijani border; an interesting cover. Azerbaijan was concentrating its monitoring of Iranian movements near the Iranian border, not the southern shores of Baku.

The third group, French business people, were already in place in Baku, making it very clear they were interested in increased French influence in the Southern Caucasus. A deep background check by Azerbaijani intelligence might suggest some of these businessmen were of Armenian heritage. Still, with their close association with the French Embassy and their military attache, no suspicion was generated. This group made initial contacts with Azerbaijanis in both Malta and Germany, and it was clear they were interested in participating in Baku’s Caviar Diplomacy. Azerbaijan’s seedy, corrupt underground is full of opportunities, such as “handing out” advanced placement in chemistry and chemical engineering at French universities. Narimzade, the deputy head of security at Penitensiar Xidmətin 10, had his lazy son rejected from Azerbaijani Technical University. The nepotism pervasive in Azerbaijani resulted in the position of gas service manager at both Penitensiar Xidmətin 10 and 11 for Narimzade’s brother-in-law. Narimzade would collect handsome fees as the intermediate between these French and potential students. Among other things, the French gave the impression they needed to know that the transfer schedule for prisoners over the next month as proof of Narimzade’s commitment and as advanced info. The French were to add lip service to human rights issues in Azerbaijan using Azerbaijani’s prisoner transfer regime. The French insisted that Narimzade’s brother-in-law set up a small gas explosion targeting political prisoners in transit, hopefully wounding only the political prisoners, not the Armenian POWs.

Regional Map White lines are incursions into Azerbaijan, red lines are general escape directions, black lines are diversions. Red dotted lines are undisclosed activity or travel on foot.

Unfortunately, there was no place to practice a Baku infiltration. The mini-submarine was a one-way trip. The French could come and go, and they did. Jiko and his Arab-speaking Armenians were the only groups that could function somewhat autonomously.

The Azerbaijani-speaking Armenians quickly made it onshore, but two were contaminated with partially enriched U235 powder from transport containers left in the Iranian mini-sub. This contamination set off radiation detectors near the Baku Marriot Hotel complex. Eventually, these two were released as they pleaded ignorance. Where they ultimately ended up was never known. The other five made it to the dual prison transfer time and place, except only one prison was transferring prisoners. A minor gas explosion diversion caused enough panic that two Armenian POWs were extracted, and several political prisoners escaped. The latter provided enough diversion for the Armenian POWs to hide in a medium-size van, change their clothes, and split up into two smaller cars. One car headed along the coast toward Russia’s Daghestan, the second one drove toward Armenia’s Tavush border area. It was through the Tavush region, where Jiko’s group entered Azerbaijan. The second car drove to the east of Nagorno-Karabakh, heading northwest. The first car made it to Russia’s Daghestan border, where they were waved through after having picked up three of Jiko’s commandos near that border. The car headed towards the Black Sea coast. The Tabriz Armenians were let off in a nondescript Daghestani village and would make it back to Iran through Turkmenistan. The second car drove to a secluded Russian-Georgian border area and headed into Georgia by foot. Three of Jiko’s guys and a POW gave themselves up to Georgian police near the Chechnya border. This diversion worked well with all three requesting political asylum in Georgia.

A general alert was sent to regional governments about the escape of an “unknown number” of Armenian POWs. Georgian police contacted Baku after they detained the single POW and Jiko’s fighters. Armenian authorities were also looking for some vehicle rumored to be driving north in Azerbaijan toward Tavush.

With soldiers and drones, much of Azerbaijan’s borders were more or less covered, but the Azerbaijani northwest/Armenia’s northeast border became the responsibility of Armenian authorities. Turkish satellite imagery shared with Baku suggested several cars were heading north for many kilometers past Nagorno-Karabakh, one near Armenia’s Voskepar. Baku gave this piece of Turkish intelligence to the authorities in Yerevan with the caveat that Ankara expects Armenia to capture the POW and any infiltrators. Ankara was particular and stated that any pending contracts with Armenian officials when their common border was open would be reviewed if these infiltrators were not apprehended. The car stopped near the Joghaz reservoir in Azerbaijan across from Voskepar. The Tabriz Armenians got out, and at dusk, walked across the Armenian border at old Voskepar. They split into two groups. One headed south toward the agricultural region hiding in a hothouse. The other group began walking north through a series of villages. They were eventually stopped by Armenian police and, with forged documents, made their way to Yerevan and eventually back to Iran. The car at Joghaz reservoir picked up what remained of Jiko’s men hiding in abandoned homes and headed towards the Georgian border near Tekali. They left their car and walked across an unsecured border section at night, where they eventually met up with contacts from Ajaria after well over a day hiding in an old truck.

Turkish intelligence was expecting the remaining POW and infiltrators to escape aboard a ship leaving either the Georgian ports of Poti or Batumi. since anonymous reports in the European press claim the POWs were in Adjaria. Instead, the POW and Jiko’s escorts were already in Armenia having been taken across an unprotected border area near Ninotsminda, Georgia.

For weeks, Armenian authorities, having received tips from regular citizens, searched for the POW and what remained of Jiko’s men. Baku threatened to cancel all contracts made with Armenians regarding interstate transportation routes and border properties. Armenian diplomats issued rubber-stamped updates to the international press. The Armenian government was scrambling since Baku suspended all transportation projects with the new class of Armenian oligarchs’ finances in suspension. Azerbaijani President Aliev was facing pro-nationalist, anti-government protests with hundreds jailed daily. Armenian PM Pashinyan reiterated how irresponsible these outside “Armenian terrorists” were since Armenian POWs are an Azerbaijani issue. Aliev began urging Azerbaijani oligarchs to pressure their Armenian counterparts, threatening them by exposing their off-shore shell companies and canceling border real estate contracts. Baku quietly enlisted the help of Israel’s Mossad, claiming an Iranian violation Azerbaijani sovereignty, but didn’t receive much actionable intelligence as Israel was more interested in seeing if Armenians could pull off this rescue, having a history of successful hostage extractions.

Speeches in the Armenian Parliament began to sound dire with near daily fist-fights between pro-government and all opposition group parties. The oligarch-funded Armenian media began demanding ordinary citizens keep their eyes open for the POW and Western Armenian-speaking Armenians. When the government announced a 10M AMD (~$21K) reward for information leading to the apprehension of this POW, there were so many tips offered on the first day that Armenia’s central mobile phone provider’s system crashed for several hours. The citizen frenzy was overwhelming.

Nobody noticed a small protest in front of the Armenian Foreign Ministry by what appeared to be an extended family, huddled together. Indeed, it was the family of the Armenian POW hiding in Armenia. The outraged family was trying to revoke their Armenian citizenship without success since the totality of the Ministry’s efforts were directed toward the apprehension of a 21-year-old Armenian POW in Armenia.

Yerevan, Armenia

Author: David Davidian (Lecturer at the American University of Armenia. He has spent over a decade in technical intelligence analysis at major high technology firms. He resides in Yerevan, Armenia).