By Nahal Sheikh

The borders of United Kingdom are probably one of the most complicated issues of what Brexit’s aftermath has produced. Once the UK voted to leave the EU, it mainly meant it could now possess more control over its borders and be able to decide who steps in and goes out.

As part of the EU, Britain has historically defined its borders as ‘soft’ despite having complicated border regulations – as compared to other European countries. However, Brexit will now place the UK as a country with ‘hard’ borders. ‘Hard’ means militarized borders that define official separation through security barriers. They do not allow for open access so things like easy traveling and free trade have many limits.

The hard border phenomena will most likely have serious consequences for its overland border – between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Especially since the border has acted as a symbol of peace for decades. Any threat to it could potentially result in dire implications that UK may not be able to recover from.

A little Irish history

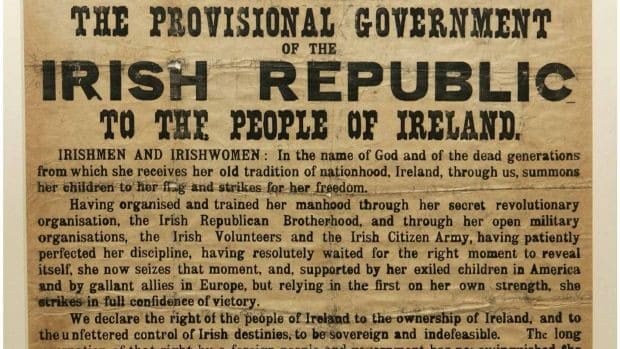

This border was first drawn by the British in the 1920s. They had been ruling the land for centuries prior to. There was historical oscillation of Irish rebellion against the British, amongst whom some part of the Irish population did not exactly wish the British demise. These dynamics led to the island’s division in two parts – Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. In the former, the population was mainly Catholic, known as the ‘Nationalists’, obvious as to how they wished for independence as the ruling majority of the island. Whereas, Northern Ireland was predominantly Protestant and identified more with British identity having situated right across the water – known as the ‘Unionists’.

Eventually in the 1940s, the South ventured to independence and became a country of its own. Overtime, hostility between the North and South grew. The hostility was not only physically violent but translated into economic backlashes such as trade wars. For example, tariffs were placed on steel, coal and agricultural goods. Relations grew more violent towards the 1960s when extremism spur out. Paramilitary nationalist groups, like the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), grew aggresive as they believed that Northern Ireland truly belonged to Ireland and that the British were unjustly trying to take control. In retaliation, Unionist paramilitaries adopted violent tactics that left them both in rising death tolls. The era is also known as ‘The Troubles’, a three-decade long bloody conflict where over 3,600 people were killed and around 50,000 injured, majority of whom were civilians.

How does the UK play part into Ireland’s bloody history?

The UK in turn funded defense for Northern Ireland because of which it was a constant target by the opposition. Over the years, the UK invested in securing the border endlessly by building up walls, towers, strong patrols and gun barriers. Anyone going in and coming out of the border was screened thoroughly ensuring no possibility of violent infiltration takes place. This transformed the border into a hard border.

Finally, in 1998, the Nationalists and Unionists decided there was no choice left but to come to a peace agreement. This was known as the ‘Good Friday Agreement’. It stated that, first, Northern Ireland will remain the UK but Northern Irish people will be eligible for both British and Irish citizenship if they wished so. Second, Northern Ireland could vote at any point in time to join Ireland. The agreement signified that the hard border relations were no longer needed, with the British military leaving the border after over 38 years. The free access in and out of both parts of Ireland symbolized years of blood and tears that went into reaching a consensual agreement that both peoples yearned for peace.

Brexit, oh no!

Once Brexit happened, the decades-old Irish troubles came back on the surface – at least in political and public discourse. Realizing the implications of Brexit, overwhelming majority of Northern Ireland was in favor of remaining – about 56 percent. So, what are these implications? As the UK will no longer remain in the European Union, its borders will once again become hard borders. Will it send back troops to the Northern Ireland border? Set up patrols and barriers? Or merely let things be the way they are by using the defense that part of Ireland is technically British and does not require the same rigid rules as the rest of UK?

The former Irish president, Mary McAleese sums up the problem eloquently:

If Britain removes itself from the EU, the only land border between the UK and Europe will be the land border between Northern Ireland and Ireland. The hardening of the border will send all the wrong signals.

The foreseeable options are such: UK could reimpose a hard border by re-entering with the border walls, police, security and checks. Or they could completely leave out Ireland and only set hard borders around the traditional British island. In both cases, either the Nationalists or the Unionists would be isolated and left with a feeling of disenfranchisement. Where will they put the hard border after all? If both the Nationalists and Unionists are concerned for their own path to isolation from the EU and the world, the most plausible option could be to enter into reunification. This option would also be line with the Good Friday Agreement. This means Ireland as a country in its own presence would no longer be burdened with Brexit’s follies, and be able to construct its own identity independent of Britain’s historical influence.

(The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of World Geostrategic Insights)