By Anton Evstratov

After the success of Turkey’s main ally, Azerbaijan, in the 44-day war in Nagorno-Karabakh, and amid the economic crisis on its territory, Ankara seeks to increase its economic and political influence in Central Asia.

The key point here is to speed up the interaction with China and increase the transit attractiveness of Turkey, which will happen after the unblocking of transport corridors in the South Caucasus. It was the key point of the joint statement of Putin-Aliyev-Pashinyan of November 9, 2020, that is of the greatest interest to Ankara, which seeks to facilitate the work of the “Middle Corridor” going through the Turkish territory, coming from the PRC and Central Asia, since now it has the ability to use the local Nakhichevan transport corridor. The latter connects Turkey through Nakhichevan and Azerbaijan with the Caspian basin and further Central Asia and facilitates the movement of goods, and also makes it cheaper, both from East to West, and in the opposite direction.

The Nakhichevan corridor reduces the length of the route from Azerbaijan to Turkey by 340 km in comparison with the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway that operated until now, and at the same time removes a significant part of the load from it, providing additional opportunities for the transportation of goods. It is obvious that the unblocking of the path will be carried out with an eye to international trade, and by no means only bilateral, Azerbaijani-Turkish.

Restoring the railway connection with Nakhichevan and Azerbaijan for Turkey will cost no more than $ 300 million, which is quite acceptable for Ankara. Taking into account the Chinese interest in the project of the Middle Corridor, it is possible to predict a quick attempt to put the Nakhichevan branch into operation.

The “Middle” or “Middle” corridor is one of the three land routes included in the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, and runs from China through the territories of the Central Asian states, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey. In 2015, a Turkish-Chinese memorandum was signed along this path, and in 2019 Ankara received $ 1 billion from Beijing for the implementation of the project. The project began to work at the end of 2020.

In this context, the position of the Central Asian countries is especially important for Turkey – this is especially true for the Turkic-speaking Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The visit to Tashkent, Ashgabat and Bishkek of Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu on March 6-9, 2021 was subordinated to the goal of rapprochement of positions on transport issues. With the leadership of Kargyzstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, the head of Turkish diplomacy discussed not only economic, infrastructure and transport issues (according to which the parties reached mutual understanding), but also the possible supply of Turkish military equipment, which has proven itself in Nagorno-Karabakh, to these countries.

Moreover, on February 23, a trilateral agreement (Ankara-Ashgabat-Baku) was signed with Turkmenistan, envisaging joint exploitation of the Druzhba gas field, and a plan for further joint exploration of hydrocarbons in the Caspian basin was outlined. Thus, jointly with benefit, the previously existing Azerbaijani-Turkmen contradictions over gas production in the Caspian Sea are largely leveled.

And just 2 months after the end of hostilities in Karabakh, Turkey signed a new trade agreement with Azerbaijan, which indicates Ankara’s direct and initial interest in the second Karabakh war as an indispensable condition for unblocking transport routes in the South Caucasus and in the future. construction of a common Turkic trade, economic and transport space – up to the border with China.

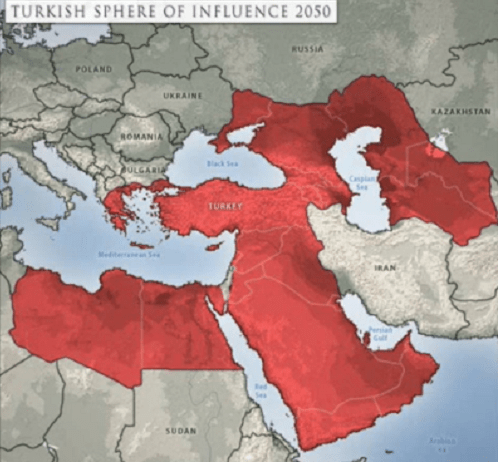

Turkish aspirations have also been illustrated by the media – Turkish TV channel TRT1 has charted an expansion of Turkish influence by 2050, which includes territories from Greece to Kyrgyzstan. A number of Arab countries and, what is especially dangerous and resonant, Russian regions (Astrakhan region, North Caucasus, Kuban and Crimea) fell on this map.

The latter caused a rather serious resonance in Russia, although Moscow realized the danger of expanding Turkish influence in the South Caucasus and Central Asia from the very end of the war in Nagorno-Karabakh. And if in the South Caucasus this expansion can be suppressed, including by force (Russian troops are in Armenia, as well as in unrecognized Abkhazia and South Ossetia), then in Central Asia Russian foreign policy has fewer opportunities to resist Turkish plans, and it is forced to act more collected and faster.

It is in this context that the talks between Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and his Turkmen counterpart Rashid Meredov on April 1 of this year should be perceived. Moscow’s goal in the course of these consultations was, obviously, to prevent Ashgabat from leaving the mainstream of Turkish foreign policy – especially against the background of the aforementioned agreements of the latter with Ankara. For Moscow this year, the agreements between the country from the zone of its strategic interests with a NATO member state (which in the case of Turkmenistan also means Turkey’s access to the Caspian basin) cannot but be perceived painfully.

Russia is also not satisfied with the possible expansion of Turkish-Chinese cooperation – through the territory of the Central Asian states. Such cooperation, on the one hand, hinders the realization of Moscow’s economic and political goals, and on the other hand, it redirects the transit of Chinese goods from the Northern route (through the territory of Russia) to the Middle (through Central Asia, Azerbaijan and other countries). And the Russian Federation has reason for concern – on March 25, the head of Chinese diplomacy Wang Yi met with the leadership of Turkey, including the president Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Russia, in turn, has common political interests and tasks with Ankara (mainly in the context of the construction of a Eurasian space and a political, geostrategic and metaphysical pole, alternative to the West) and economic projects, the main one being the Turkish Stream, therefore, does not intend to drastically ruin relations with Turkey, while striving to limit and reduce its influence in regions that are strategically important to itself.

The expansion of Turkish influence both in Central Asia and in the South Caucasus is no less dangerous for Iran’s interests. The latter negatively perceives this scenario, fearing, on the one hand, to be cut off from Armenia and Georgia by the “Turkic belt” formed on its northern borders, and on the other hand, he is not ready to tolerate strengthening. its boundaries.

At the same time, Tehran did not provide any assistance to Armenia and Artsakh in their war against Azerbaijan and Turkey, because, on the one hand, it is not a principled opponent of the restoration of Baku’s control over Nagorno-Karabakh, and on the other hand Turkish diplomacy offered Iran its refusal to join the US anti-Iranian sanctions in exchange for neutrality. However, the new realities of the South Caucasus and Central Asia are more dangerous for Tehran than they were before the 44-day war, and it will have to tackle new problems with much more caution and effort.

Thus, we can state an obvious increase in the role of Turkey, both in the South Caucasus and in the general Eurasian politics after the 44-day war in Nagorno-Karabakh. The main goal of such a policy for Ankara at the moment is the Turkic states of Central Asia, which at first glance have many benefits from this process – strengthening cooperation with Turkey will give them both benefits from bilateral trade, and income from Chinese transit, and investments, infrastructure modernization, diversification of the economic, political, and, in the long term, military influence of Beijing and Moscow. On the other hand, the results of the conflict in Karabakh gave these states an example of partnership with Turkey with Azerbaijan – an extremely controversial example. On the one hand, Ankara supported its partner and ally in its conflict with Armenia and Artsakh.

However, here Ankara defended its geostrategic and economic interests – especially against the backdrop of the economic crisis and difficult relations with the United States. On the other hand, it has put its partner and ally into an almost complete military-political dependence on itself. From the very beginning of the war in Nagorno-Karabakh, the Azerbaijani General Staff is led by Turkish officers, the Azerbaijani army is entirely dependent on the supply of Turkish weapons and military specialists, and the subjectivity of President Ilham Aliyev has decreased so much that even the fate of Azerbaijan, in fact, is decided through Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Whether the countries of Central Asia are ready to play such an Azerbaijani role in relations with Turkey is an ambiguous question. If the economically and politically weak Kyrgyzstan, and especially Turkmenistan,can theoretically agree to be linked to Turkey (although Kyrgyzstan simply will not be able to realize this scenario due to strong Russian and Chinese influence), Uzbekistan, and especially the richest country in the region, Kazakhstan, have their own regional and world interests, and the role of a Turkish vassal is poorly suited. Turkey’s panturanistic projects have one significant drawback for its partners – their center of gravity always falls on Ankara, which claims to be the leader of the entire Turkic world.

The states of Central Asia, in addition to the influence of other world centers (China and the Russian Federation), have their own interests and long-term, medium-term and short-term goals, contrary to the ideas of Turkish strategists and, in general, they do not intend to give up sovereignty and be satellites of Ankara. Furthermore, none of the countries in the region have a military conflict that requires Turkey’s resolution and protection. In turn, Ankara’s penetration into Central Asia, critically perceived by Russia and China, will inevitably cause opposition from the latter, raising also consequent economic problems, unwanted by those already in a difficult socio-economic context, such as Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan, nor for those states that aspire to regional leadership and greater subjectivity, such as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Author: Anton Evstratov (Russian historian, publicist and journalist living in Armenia, lecturer at the Department of World History and Foreign Regional Studies at the Russian-Armenian University in Yerevan).

(The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of World Geostrategic Insights)