By Alvin Cheng-Hin Lim

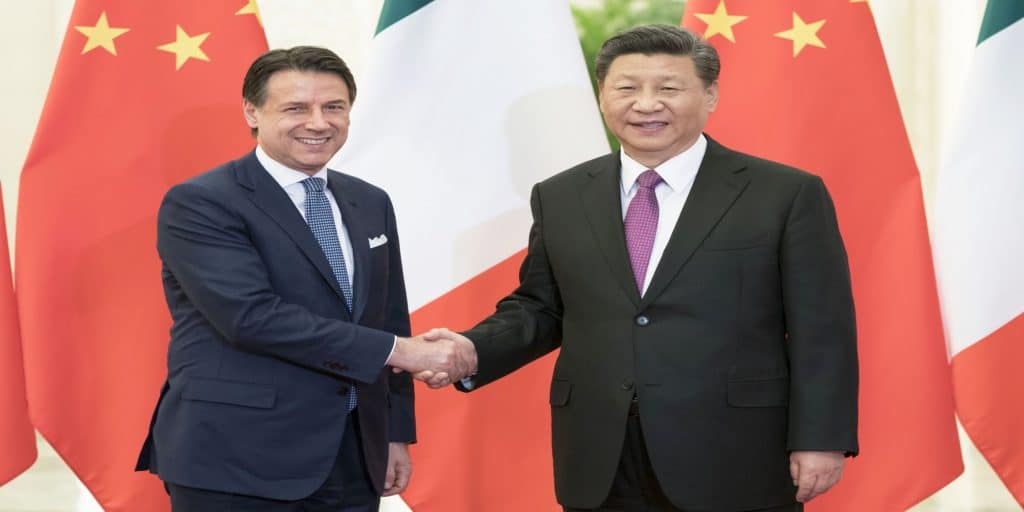

On Saturday March 23, 2019, during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s state visit to Rome, Italy formally joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with the signing of an official Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between both countries. This marked a significant milestone in the growth of the BRI.

While 13 other member states of the European Union (EU) had already joined the BRI, including Greece and Portugal within the past year, Italy was the first G7 country to do so, and is now the largest economy to have joined the BRI. This major development in international relations has sparked consternation among critics of the BRI, especially given Italy’s key position within the leading EU countries. These critics wonder: will China use Italy as a Trojan Horse to deepen its penetration of the EU?

The Sino-Italian MOU serves as a framework agreement for 29 deals valued at almost 3 billion USD, with a commitment for potential project funding of up to 20 billion USD. These deals are in a range of sectors including agriculture, aviation, environmental protection, finance, healthcare, oil and gas, sustainable energy, and urban development.

While the terms of the MOU are non-binding, the MOU demonstrates the intent of both governments to strengthen Sino-Italian cooperation with the building of deeper economic and social ties. The Italian government is especially keen to reverse the declining flow of investment from China and to reduce its 12.1 billion USD trade deficit with China. The hope for the Italian government is that the anticipated increases in Chinese investment as well as exports to China will provide much-needed boosts to the Italian economy which has been in a recession since last year.

From a longer-term perspective, the strengthening of Sino-Italian relations under the BRI would mark a major milestone in their long East-West friendship. As Xi Jinping observed in his signed article in the Corriere della Sera that was published ahead of his state visit: “Friendly ties between our two great civilizations go back a long way. As early as over 2,000 years ago, China and ancient Rome, though thousands of miles apart, were already connected by the Silk Road.”

For China, Italy serves as a major gateway into the EU. In particular, Italian ports such as Venice, Genoa, Trieste, and Ravenna present strategic access points to shipping routes along China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, the major maritime axis of the BRI. For Italy, the Chinese redevelopment of the Greek port of Piraeus shows the promise of what could happen with its ports. Under the Chinese, Piraeus has become the busiest port in the Mediterranean, and this in turn has led to significant job creation for the local economy.

While critics have voiced concern that the Chinese will take control over Italian ports the same way they took over Piraeus, the Italian government has stated that this will not happen since Italian law prohibits the foreign takeover of the country’s ports. Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte has likewise addressed the Sinophobic fear that Italy will become a Chinese Trojan Horse, noting that the Sino-Italian MOU completely adheres to EU policy including the 2020 EU-China Cooperation Agenda.

Another fear that critics have is of Italy falling into a Chinese debt trap. The critics point to the example of Sri Lanka, which lost its port of Hambantota to Chinese control following its government’s failure to meet its debt obligations to China. Michele Geraci, the Italian

Undersecretary of State for Economic Development, has addressed this issue, noting that the Italian government has not sought funding from China and as such is not at risk of falling into a debt trap.

A different concern for the Italian government is the gap between what was promised and what will be delivered from the BRI. Countries such as the Philippines as well as those in Central and Eastern Europe that have joined the BRI have experienced disappointment with the actual levels of BRI investment in their economies, especially when compared with the vast amounts that were promised.

The problem arises from the non-binding nature of the MOUs signed between China and its BRI partners, as there is no penalty should China fail to deliver on its promised investments. Actual investment from China only arrives when the government agencies and companies concerned agree on the bilateral projects and their financing arrangements. This means the actual level of investment may be much less than what was originally hyped, and if that happens, the government may have to suffer the political consequences of disappointing the public.

Apart from concerns from the EU, the Italian government has also faced domestic resistance over its decision to join the BRI. Matteo Salvini, the Italian Deputy Prime Minister and leader of the League, one of the Italian government’s coalition partners, conspicuously absented himself during Xi Jinping’s state visit, having earlier warned of the risk of the Chinese colonization of Italy. Salvini’s performative disapproval could be a harbinger of future domestic resistance to China’s planned BRI investments in the country, especially in the area of port redevelopment.

The US, which is mounting a stiff challenge to China’s global ambitions, has also applied strong pressure on the Italian government to desist from joining the BRI. While Italy was obviously not deterred from joining the BRI, the Sino-Italian MOU did not include an agreement on Chinese investment in Italy’s 5G telecommunications infrastructure.

This was likely due to US pressure on its allies to reject 5G technology from Chinese vendors like Huawei. Italy’s tightrope act between the US and China could also be seen in Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte’s attendance at the April 2019 Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, in which he only arrived after the opening ceremony, and in which he conspicuously avoided wearing the official Belt and Road lapel badge.

These symbolic actions demonstrated that while Italy has joined the BRI, the Italian government does not yet fully align itself with China.

(The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of World Geostrategic Insights)

Image Credit: Italian Presidency of the Council of Minister