By Anton Evstratov

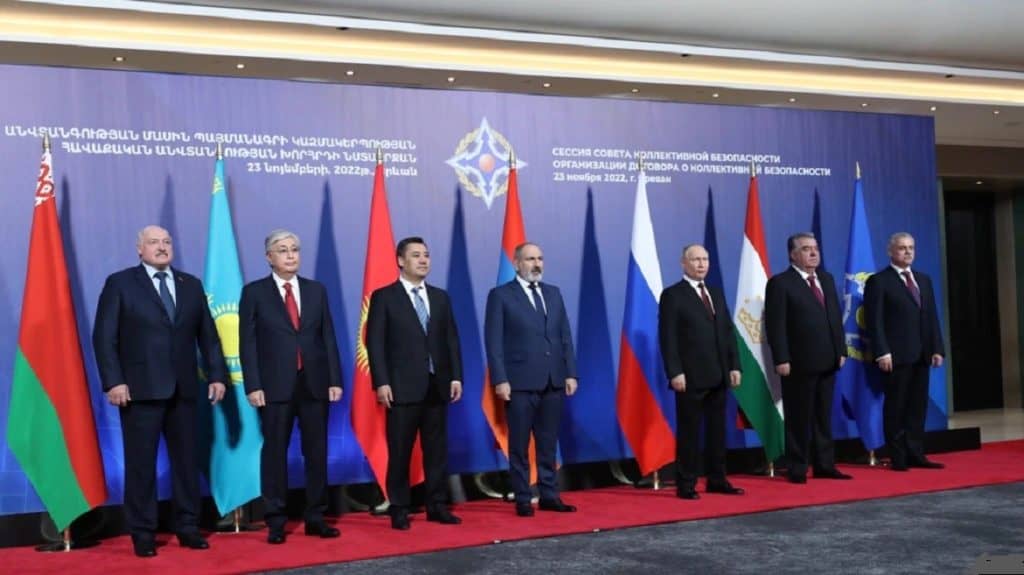

The Russian special operation in Ukraine has raised a number of uncomfortable issues for the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the intergovernmental military alliance in Eurasia of six post-Soviet states: Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan. However, the organization still has the resources to resume its activities.

The Russian-led CSTO bloc has undergone a number of trials in recent years. First, the Armenian-Azerbaijani and Kyrgyz-Tajik conflicts, the unrest in Kazakhstan, and the Russian special operation in Ukraine. It is extremely noteworthy that the bloc’s response was only truly effective in the winter of 2022 in Kazakhstan, when the CSTO not only managed to manage the unrest and provide concrete assistance to President Kasym Jomart Tokayev and his administration, but also ensured the collective representation of member countries in this operation and, after its completion, without technical or political excesses or problems, to withdraw troops from Kazakh territory. However, this mission, having a specific nature, is perceived both in Kazakh society and in the intellectual environment of member states in an extremely ambiguous way.

At the same time, in the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, which has long not been localized in Nagorno-Karabakh, which is not part of the official jurisdiction of the CSTO, and proceeds quite actively in the internationally recognized territory of Armenia, the bloc’s representatives have limited themselves to formal statements and equally formal monitoring activities. Despite obvious Azerbaijani provocations and Armenia’s occupation of part of the Syunik region, as well as relatively large-scale military operations in mid-September of this year, CSTO’s governing bodies have not named the aggressor or even given open verbal support to its member country.

It is worth noting that the voices of opponents to the country’s membership in the bloc (as well as other Eurasian initiatives) had been heard in Armenia before, and after the mid-September events they could not help but resonate. Indirectly, these views were supported by high-level politicians – RA Security Council Secretary Armen Grigoryan and Parliament Speaker Alain Simonyan. In addition, Armenia refused to participate in the UCSD special forces exercise “Interaction 2022.”

Similar was the reaction of Kyrgyzstan to the insufficiently adequate, in the opinion of its leadership, position of the bloc on the issue of assistance in the conflict of this state with neighboring Tajikistan. The main problem here is the fact that both countries are members of the CSTO, and the latter simply cannot unambiguously support one of them. Nevertheless, it was Kyrgyzstan that canceled its participation in the command-staff maneuvers “Unbreakable Brotherhood” (even though they were supposed to take place in the country, and Bishkek’s demarche was actually the cancellation of the event in its planned form), and its President Japarov openly criticized the block at the summit in Astana. The fact that Tajik President Rakhmon, in turn, criticized Russia (albeit personally – without reference to the CSTO) at the Tashkent SCO summit adds to the criticality of the situation.

The problems of Kyrgyzstan, Armenia and Tajikistan in the CSTO are even more shadowed by the extremely active American and Western diplomacy in and around these countries. Thus, it was after the CSTO’s inarticulate reaction to the events in Armenia that U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited the country. And even though her visit was a private one and lacked any real consequences apart from some verbal statements, many in Armenian society perceived Pelosi’s trip as an indicator of Washington’s readiness to replace Russia in the resolution of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict. Even the subsequent statements by the United States about its readiness to provide military assistance to Armenia’s enemy, Azerbaijan, in case of its conflict with Iran (remember, the United States has never promised military assistance to Armenia), did not completely change the extremely negative discourse with regard to the CSTO and Russia’s role in the region as a whole.

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, in their turn, were invited by the Americans to the multilateral exercise “Regional Cooperation-2022” where Kazakhstan was also invited. In total, this year the US Department of Defense budgeted $500 million for various programs of military cooperation with the post-Soviet countries of Central Asia. It mainly concerns assistance to these countries in anti-terrorist activities on and near the Afghan border, but the regional players receive from the US, for example, air equipment, which gradually undermines Russia’s monopoly in this field.

Russia’s hands are seriously tied in responding to these and other challenges for the CSTO by its special operation in Ukraine, which obviously required more resources than originally planned. Currently, Moscow needs to ensure at least temporary stability in the territories of its sphere of influence at any cost, to “freeze” the events there so that after dealing with Ukraine, it can turn to the problems of other regions. This explains, for example, Russia’s concessions to Azerbaijan and Turkey standing behind it – a key player in the current geopolitical and geo-economic scenario. At the same time, the very dependence of all CSTO members on Moscow in different spheres sometimes pushes it to rather rude, authoritarian actions against them, which does not add to the Russian side’s sympathy.

As a result, none of the CSTO countries, with the exception of Belarus, openly supported Russia in its Ukrainian special operation (and the accession of four new regions to Russia was not publicly supported by Minsk either), putting into question the future prospects of the organization. At the moment, it is obvious that all members of the bloc are striving to achieve maximum loyalty from Moscow under the existing conditions, on the one hand, and to maintain relations with NATO, the EU, the USA and the West in general at the previous, sufficiently high, level, on the other hand. In particular, such aspirations are reflected in Kazakhstan’s new military doctrine, which calls for diversifying military purchases and responding to the widest range of military and political threats. It should be noted that the Russian special operation in Ukraine has in a sense alerted Moscow’s allies, who fear that sooner or later they will share the fate of Kiev, while not the most successful actions of the Russian army in recent times have dealt a blow to the credibility of the Russian Federation.

Despite the obvious difficulties of the CSTO as an organization and of Russia as its leader, as well as the exhortations by some experts that Russia is withdrawing from its zones of influence, not only are they likely to maintain the status quo in the short to medium term, but they also have chances of resetting the bloc and Russian influence in Central Asia, the South Caucasus and Eurasia as a whole.

First, a decisive victory of Russian troops in Ukraine would immediately close a number of issues, from Moscow’s credibility, to freeing the attention of the Russian leadership from the Ukrainian issue. Militarily, this outcome is possible – both through extensive efforts (broad mobilization and large-scale combined arms offensive in different directions) and intensive efforts (skillful actions of the new command in the winter campaign, or the use of new weapons, including tactical nuclear weapons).

Second, there is now, on the one hand, Iran’s desire for maximum integration into Eurasian structures and, on the other hand, the extremely positive experience of Russian-Iranian military and economic cooperation during the Ukrainian special operation.

The inclusion of Iran in the CSTO would be a logical step in the direction of Russian-Iranian rapprochement and could have a very positive impact on the prospects of the organization, on its authority, and on the geography of its military and political efforts. Such a scenario would make the bloc truly Eurasian, and the resources of the Islamic Republic and its influence in Tajikistan and the Caspian Basin and the Middle East would not only help to retain its existing members, but possibly attract new ones. Undoubtedly, this kind of integration will put Russian-American contradictions on a new, much more confrontational level, and it is this prospect that ties further developments to the political will of the Russian political leadership.

Author: Anton Evstratov (Russian historian, journalist and journalist living in Armenia, lecturer at the Department of General History and Foreign Regional Studies at the Russian-Armenian University in Yerevan).

(The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of World Geostrategic Insights)