World Geostrategic Insights interview with Mark N. Katz on the significance of the UAE’s mediation in the Russian-Ukrainian POW exchange and Putin’s visits to Abu Dhabi and Riyadh, whether Russia can still aspire to a global superpower role, the issue of the Russia-China-Iran joint military exercises in the Gulf, and the current state and prospects of Russia-Israel relations.

Mark N. Katz is a professor of government and politics at the George Mason University Schar School of Policy and Government, a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, Washington D.C., and the Chairperson of the Scientific Advisory Council Finnish Institute of International Affairs.

Q1 – On Wednesday, January 3, the first POW exchange between Russia and Ukraine in about five months took place, mediated by the United Arab Emirates. With more than 470 prisoners released, it can be considered one of the largest exchanges of military forces in the Russian-Ukrainian war. The UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs said the operation was made possible by the “strong and friendly relations” with Moscow and Kiev and expressed willingness to make further efforts to end the war. How do you comment on this news? Considering that it comes after Russian President Vladimir Putin’s “working visit” to the UAE and Saudi Arabia on Dec. 6, can it be seen as evidence and a result of the growing intertwining of diplomatic influences and political and economic relations between Russia and the Arab world?

A1 – The United States, other Western governments, and Ukraine have been unhappy with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) for enabling Russia to evade Western sanctions through buying Western goods through the UAE and for its overall continued cooperation with Moscow.

The UAE’s ability to mediate a Russian-Ukrainian prisoner exchange enables Abu Dhabi to argue that its continued good relations with Moscow has been beneficial to the West, and indeed, that Russian-held Ukrainian prisoners might never have returned to Ukraine without the UAE’s help.

The possibility that the UAE can help facilitate further such prisoner exchanges can be used by Abu Dhabi to persuade the West that the UAE’s good relations with Russia can be helpful both to Ukraine and the West—and so Washington should not undertake measures punishing the UAE for its trade with Russia. Abu Dhabi may also hope that the UAE’s usefulness to Russia will incentivize Moscow to not support Iranian actions that the UAE considers threatening.

The UAE’s ability to mediate between Russia and Ukraine, though, is only an indicator of the strength of Russia-UAE relations, and not Moscow’s broader relations with the Arab world.

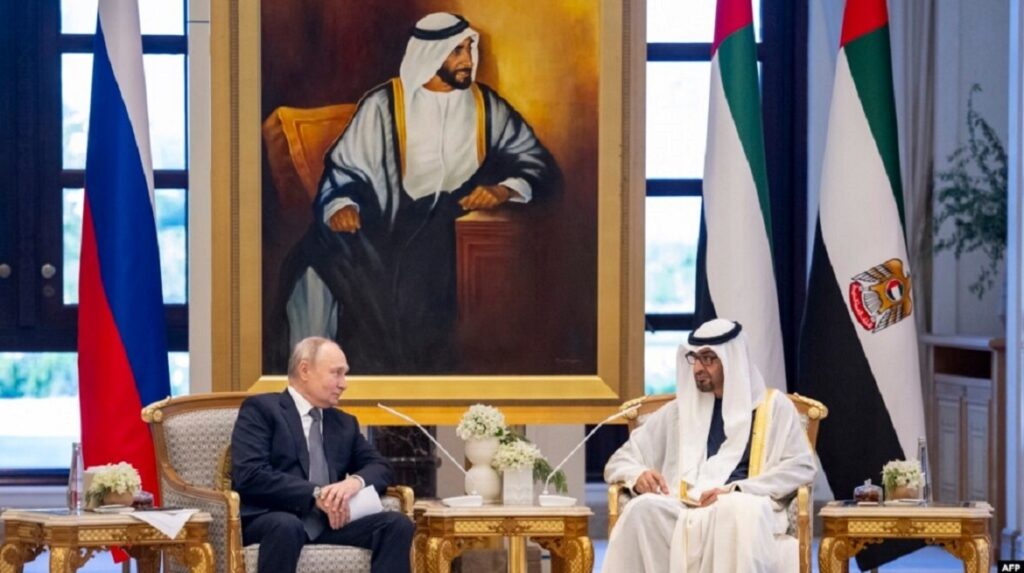

Q2 – According to many international political observers, Putin’s trip to Riyadh and Abu last December, beyond the political and economic agreements reached, could represent an important milestone in Russia’s current foreign policy, with significant repercussions on domestic politics as well. Indeed, with the trip and the warm reception received by the leaders of the Gulf countries, Putin made it clear that Russia not only plays an active role in the post-Soviet space but, despite the conflict in Ukraine, remains influential in several global theaters. In particular, Putin showed that there is a part of the Planet, the so-called Global South, that does not want to keep him isolated, and does not want to break with Russia. This may be important also for domestic political purposes, to show Russians that Putin is not a pariah in the international arena, but is considered as such only by “Russia’s enemies”, namely the West, which could be an important argument in the run-up to the new presidential elections. What is your opinion?

A2 – Putin’s successful visits to Abu Dhabi and Riyadh may well serve to bolster Moscow’s claim that only the West is against Russia, and not even America’s traditional partners in the Global South (such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE) are not. I’m not sure, though, how important this is for Putin’s domestic standing, as there is no doubt that he is going to prevail in the upcoming presidential election whether he visited these two Arab countries or not. Putin, I think, would be happy if his good relations with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi helps exacerbate relations between them and the West.

Q3 – There is more and more talk in the countries of the so-called Global South about the possible transition to a new world order, no longer unilateral, and therefore led by the United States, but rather multipolar. What is your opinion? Does Russia still have a dimension as a key global player in the world? Do you think that despite the aggression against Ukraine, the clash with the West, and the severe weakness of its economy, Putin’s Russia can still aspire to be one of the key poles of an eventual new multipolar order?

A3 – In my view, the unipolar world is something that never really existed. It was an image created when the end of the Cold War left the US as the world’s most powerful actor, but even then it was clear that Washington was unable to control the world successfully. It was also clear for all those who cared to notice that other powers were trying to assert themselves. As some of these powers have become more active than they were (China, India, and Russia in particular), the world now appears more multipolar. But while the “Global South” may think a multipolar world order is somehow better or fairer, it is important to note that the Global South as a whole is not a great power, but an arena in which great powers act, even though some of those great powers—China and India—are from the Global South themselves.

Russia’s ability to act as a great power, though, would seem to be limited. The demands of the war in Ukraine mean that it cannot spare many troops for action in the Global South. Indeed, Russia’s ability to continue selling weapons to the Global South has been constrained by Russia’s own need for them. The weakness of the Russian economy–especially compared to more robust ones in China, India, and elsewhere in the Global South–will also put Russia at a competitive disadvantage with them in any contest for influence.

Q4 – As the war in Gaza continues, and Washington is engaged in a complex diplomatic and military management of the ongoing Middle East regional crisis, Russia, Iran and China are planning joint military exercises in the Gulf region.In your opinion, are we really facing a significant increase in the influence of the China-Iran-Russia axis in the region? A growing role of China and Russia in the Middle East could pose a challenge to the national security interests of the United States, and the West in general?

A4 – The problem with Russia and China holding joint military exercises with Iran is that this gives the Arab Gulf countries an incentive to maintain their security ties to the United States—which Russia, China, and Iran all want to see weakened. The Gulf Arabs do not see Russia and China as threats, but they do see Iran as one. So Russia and China holding joint military exercises with Iran may actually serve to limit Russian and Chinese influence in the Arab world.

Q5 – During the initial phase of Israel’s war against Hamas in the besieged Gaza Strip, Russia adopted a cautious stance, condemning the attack on civilians and calling for a comprehensive political solution. Soon after, however, Moscow’s position changed and became tougher, condemning Israeli attacks, Washington’s support for Tel Aviv, and the U.S. veto to a ceasefire at United Nations Security Council (UNSC) meetings. President Putin even went so far as to compare the Israeli siege on the Gaza Strip to the Nazi siege of Leningrad in 1941. For its part, Hamas has released all prisoners with dual Israeli-Russian nationality, without a formal prisoner exchange agreement like those negotiated by Qatar and Egypt. What is your opinion? Why has Putin compromised his strong relationship with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu by moving closer and closer to Hamas positions? Could Moscow position itself as a credible mediator in the conflict and claim a role in defining the post-Gaza war era?

A5 – Russian-Israeli relations have become strained since the outbreak of the conflict in Gaza, but both Putin and Netanyahu seem determined not to let them deteriorate too far—as was shown by Netanyahu’s asking Putin for help in seeking the release of Hamas-held Israeli hostages, and Putin’s agreeing to do so. Netanyahu, though, is not going to turn to Russia to mediate an overall settlement to the Gaza conflict. Netanyahu doesn’t want a mediator that would pressure him to make any sort of concession to Hamas.

Nor is Moscow willing or able to pressure Hamas to make concessions to Israel. Finally, Russia is not in a position to provide incentives to both Israel and Hamas for making peace the way the US has been able to in the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt and the Abraham Accords between Israel and four Arab states.

What is important to Netanyahu in the current conflict is not Russia’s potential role as a mediator, but that Russia does not provide any concrete assistance to Hamas (which it isn’t). Russian criticism of Israeli policy may be annoying to Israelis, but it is something that they can live with—and indeed have long done—while still preserving the ongoing Russian-Israeli cooperation that both sides value.

Mark N. Katz – Professor of government and politics at the George Mason University Schar School of Policy and Government.