World Geostrategic Insights interview with Fabio Massimo Parenti on the reasons behind the Italian government’s decision to exit China’s Silk Road, its implications, and the prospects for Italy-China relations.

Fabio Massimo Parenti, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of International Political Economy at the China Foreign Affairs University, Beijing, and of Economic and Political Geography at the Lorenzo de’ Medici International Italian Institute, Florence

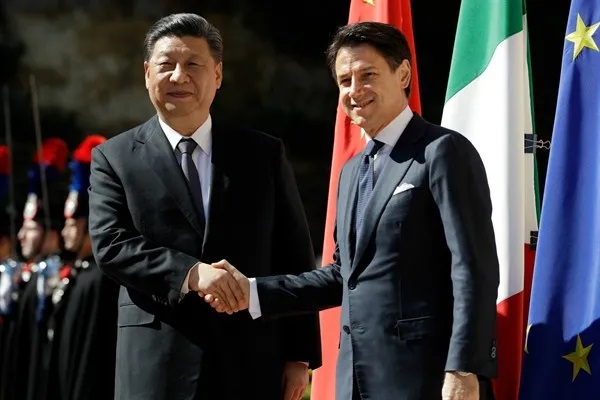

Q1 – The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as the “Silk Road,” is a major initiative launched by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, involving hundreds of billions of dollars of investment aimed at strengthening trade infrastructure and transportation networks around the world to facilitate, and expand, world trade and, as a result, also strengthen China’s presence and influence in Africa, Asia and Europe. Italy was the first and only G7 country to join the initiative and will now be the first to leave. In fact, during the recent G20 Summit in New Delhi, the President of the Council of Ministers, Giorgia Meloni informed Beijing Premier Li Qiang of Italy’s decision not to renew the BRI Membership Memorandum, signed in 2019 by the Conte government. Italy, Meloni explained, is exiting the agreement on the basis of economic interchange numbers that are not favorable for Italy, that is, on the basis of “data of merit,” “not because someone tells us so.” Italian Defense Minister Crosetto had a few days earlier declared that “The choice to join the Silk Road was an improvised and atrocious act,” while Economy Minister Giorgetti, already in the Draghi government, tried to downplay the agreement. What is your opinion? Was joining the Silk Road an improvised act of the Conte government, or did it instead respond to economic logic and Italy’s interests? What benefits were expected? Is it true that Italy did not benefit from participating in the Chinese initiative? Did Italy exit the agreement only because of unsatisfactory economic “figures of merit” or also, more importantly, because of domestic political reasons and pressure from foreign powers, particularly the United States?

A1 – Italy joined the Silk Road in March 2019, when the first Conte government was in office, formed by a majority consisting of the 5 Star Movement and the Northern League, led at the time by Luigi Di Maio and Matteo Salvini respectively. This was not an improvisation but, it seems clear, the culmination of a reasoned and well-organized process moreover approved and shared by many politicians who today oppose the project for mere matters of political convenience. Over the past 50 years, since the beginning of diplomatic relations, Italy and China have signed some 64 treaties on a wide variety of subjects. This has been consistent with actions taken by the European Community/European Union. For example, the EU and China signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in 2003, before Italy did so bilaterally, and the EU itself signed a Memorandum of Understanding related to the Silk Road in 2015. The partnership is the result of a much longer history and the 2019 BRI MoU has been a logical consequence, a continuation of it.

Italy’s entry into the BRI should have been a new starting point to consider, and to draw from, to strengthen cooperation between Rome and Beijing. It was of fundamental importance to bring Italy to the same level as countries, such as France and Germany, which without needing to join the Silk Road-because they already had strong trade ties at their disposal-can still count on an established relationship with China. Italy could have taken full advantage of this institutional framework to make up for lost time, and those who deal with China know that this path was the most appropriate.

Moreover, the reading of the data was often misleading and decontextualized. Meanwhile, because shortly after the Italy-China MoU was signed, we had a major global health emergency, the COVID pandemic, which slowed down any operational plan. After that, after the fall of the first Conte government, successive Italian executives did not move a finger to obtain benefits from the BRI: it is normal, in such a context, to make any effort, not to obtain phantasmagorical data. Finally, it is worth reading the hard data. In 2022, the trade volume between Italy and China reached $77.884 billion, an increase of 5.4 percent year-on-year. In fact, in the first five months of this year, Italian exports to China increased by 58 percent year-on-year. This allows us to emphasize from the outset that the economies of the two countries are highly complementary and that bilateral economic and trade cooperation continues to be strong, despite the years of the COVID-19 pandemic and rising international geopolitical tensions.

The BRI, as mentioned above, fits into an inherently favorable context, offering the Italian government the chance to strengthen relations with China and multiply mutual opportunities, in the economic, scientific, cultural, and numerous other fields. The signed agreements were to be the basis on which to build a win-win relationship between Italy and China. Thus, there is no “data of merit” to explain Italy’s exit from the BRI. Weighing in, if anything, is a negative geopolitical climate, exacerbated by tensions between the United States and China, with Washington repeatedly, more or less implicitly, signaling to the Italian government to withdraw from the project.

Q2 – In addition to the decision not to renew membership in the BRI, the Italian government has expressed its intention to consolidate and deepen the dialogue between Rome and Beijing on key bilateral and international issues, and to strengthen economic relations through the revitalization of the Italy-China Strategic Partnership, launched by the Berlusconi government in 2004. What is your opinion on the effectiveness of this “strategic partnership”? Is it just an attempt by the Meloni government to exit the BRI in a soft way, trying to avoid retaliation? Or could a revival of it really serve to maintain and strengthen relations with China, avoiding the suspicion of alleged BRI-related “political compromises” with China, and thus the discontent of the United States and other major allies?

A2 – On the partnership and the MoU-BRI: as written above, one is not an alternative to the other, they are not mutually exclusive in any way, and, most importantly, the path has been political across the board, from Prodi to Conte, via Berlusconi and Renzi. The MoU-BRI was the fruit of the 2004 partnership, which was equally broad and cross-cutting, reflecting an increasingly strong economic relationship in which China and the EU have become important trading partners. China is the EU’s first partner, while the EU is China’s second partner: we have lost positions in recent years, mainly due to the growth of other macro-regions, such as Southeast Asia, which has overtaken us. Also to be considered is the accession of major European economies to the AIIB, the BIS financial instrument.

If the Italy-China agreement on the Silk Road had huge strategic implications, what should we have said about collaboration in the implementation of the European Galileo satellite system? Or of collaboration in the Copernicus project? In addition to increased cooperation in aerospace, the groundwork was laid at that time for improved relations between China and the EU in the field of security and the defense industry. It is true that recently things have changed, or rather, we have been induced to change course, but we should not forget the minor weight of the 2019 MoU compared to many other fruitful forms of cooperation with China. In addition to the 23 European countries that signed the same MoU in 2015, the European Commission and the Chinese government signed an MoU for an EU-China connectivity platform aimed at strengthening synergies between the BRI and Europe’s internal TENT initiatives.

In short, we try not to fall for political marketing that misses the point. External political diktats call for our exit from the BRI, and while we suffer this absence of national autonomy China throws us a bailout donut, suggesting Meloni use the partnership. This affair might suggest the development of a book entitled “The Passivity of Italian Politics.”

China certainly has no intention of closing the doors in Italy’s face or “punishing” it by implementing retaliation, as some media have written. Beijing will take note of the Italian choice and continue to cooperate with Rome, as was the case before the BRI. One thing is certain, however: Italy cannot expect to be treated with the trust and attention that China had concretely reserved for it.

In other words, in dealing with China, the Italian government will no longer have a red carpet waiting for it, nor will it have front-row or privileged seats. This is perhaps an aspect not considered by the Meloni government, which is trying to consolidate the fragile balancing position from which it is operating: on the one hand, responding to Italy’s national interests, which would have objective advantages in maintaining and improving broad relations with new partners-especially complementary ones like China-on the other hand, not deviating too much from Atlanticist and pro-U.S. logics. That is to say: not flirting with U.S. rivals. In a war, however, this should not concern or involve Italy at all.

Q3 – Chinese Prime Minister Li Qiang said after meeting with Meloni that a healthy and stable relationship between China and Italy “is in line with the common interests of both countries and is necessary for the better development of both,” and “it is hoped that Italy will provide a fair, just and non-discriminatory business environment for Chinese companies to invest and develop in Italy. China will continue to expand market access to create more entry opportunities for quality products.” How do you expect relations between Italy and China to develop in the coming years? Will investment and trade opportunities increase? Or could there be negative repercussions in relations between the two countries as a result of Italy’s exit from the BRI?

A3 – In part, I think I have already answered that. As explained, China will continue to work to create as many mutually beneficial relationships as possible, with as many countries as possible. Italy will not end up on any blacklist; it has only missed a much-needed train to put itself on the level of France and Germany. When our politicians point out that Paris and Berlin can get lavish orders from Beijing without ever having joined the BRI, it should be explained to them that they can afford it thanks to the deep diplomatic, political, and commercial work put in place in recent years. The opportunities will remain, but without the Silk Road, the road that could have been downhill would rise to form a strenuous climb. It will be more complex. In the background, of course, we must take into account geopolitical events. In the event of conflict or war between China and the United States — an event that the Chinese government does not intend to provoke — the context would change dramatically. In the meantime, however, I am convinced that Italy will in fact remain on the Silk Road while abandoning the framework agreement. If there will be new investments, it would be about that.

Q4 – In your book “Chinese Way – Overcoming Challenges for a Shared Future,” you state that China’s growing role in the world is not a “threat,” as this country aims to achieve its economic and geopolitical goals through mutual respect, spatial interconnection, and long-term productive investment. In recent years, however, in most Western countries China is no longer seen as a trading partner, but as an adversary, a potential enemy, with whom it is necessary to do business, but with caution, and the conflict in Ukraine has helped reinforce this perception. Is it still possible to imagine a future of shared prosperity between China and the West?

Q4 – In your book “Chinese Way – Overcoming Challenges for a Shared Future,” you state that China’s growing role in the world is not a “threat,” as this country aims to achieve its economic and geopolitical goals through mutual respect, spatial interconnection, and long-term productive investment. In recent years, however, in most Western countries China is no longer seen as a trading partner, but as an adversary, a potential enemy, with whom it is necessary to do business, but with caution, and the conflict in Ukraine has helped reinforce this perception. Is it still possible to imagine a future of shared prosperity between China and the West?

A4 – It is possible, provided, however, that we stop analyzing the world by looking at it through our own lenses, those of our contemporary and modern history of de facto domination of the West over the rest of the world. This world already no longer exists today.

China continues to pursue its peaceful development by focusing on win-win and mutually beneficial relations. The Chinese approach to solving global and common problems together can only bring widespread benefits. In contrast, the West is flattened on a zero-sum game, exacerbated by a Cold War mentality that ends up dividing the world into mutually opposing blocs. The war in Ukraine has aggravated this perception, belied by reality, however. China continues to reach out to the West, and there is no shortage of issues on which to converge, from climate to poverty reduction in developing countries.

Fabio Massimo Parenti, Ph.D.- Associate Professor of International Political Economy and of Economic and Political Geography.

Text of the interview of Fabio Massimo Parenti in Italian language