By David Davidian

The following fictional Red Cell scenario is intended to stimulate alternative thinking and challenge conventional wisdom, tying together events in operational fiction with national realities

With the creation of Armenia’s new distributed government, a complete accounting of state assets was initiated. Upon inspection of the several Western-sponsored biolabs in Armenia, elite members of Armenia’s Special Security Service, known as the Black Level (BL), came across an encrypted file with an odd name, naphthenic_hydrocarbons.docx. Out of petabytes of Armenian DNA data lifted from these biolabs, this was the only file that appeared encrypted. It took forty-four days to fully crack the file because it was encrypted by a third-party application, not the firm in Redmond, Washington.

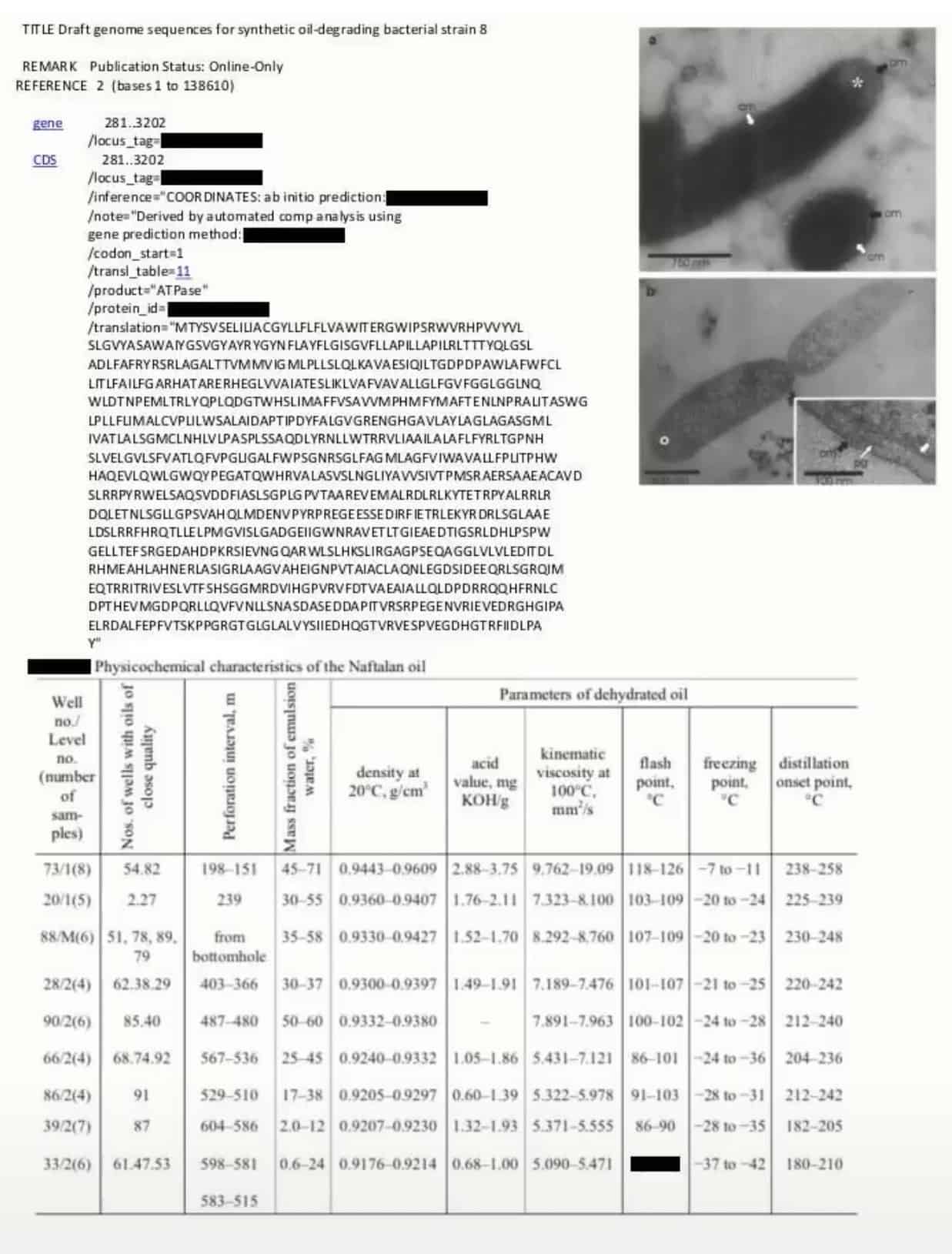

Initial inspection of this file by BL’s biochemists showed it contained the genetic blueprint for a simple synthetic bacteria. It was assumed this bacteria was somehow related to bioweapons research. However, as additional decrypted pages became available, it was clear that a secret research program was undertaken by unknown people associated with biolab3. This program was a blueprint for a synthetic bacteria that would eat Azerbaijani crude oil, specifically oil containing substantial amounts of naphthenic hydrocarbons, uniquely found in crude oil such as from the Naftalan oil wells in Azerbaijan. However, there was no indication of an active experiment program in biolab3. The documents detailed substantial research, but operational testing must have been performed elsewhere. Investigators asked themselves why? What was so secret that research was performed at one site but experiments at another? Where was this location? Was this an operation by some foreign power or a local rogue group? Certainly, it was not sanctioned by the regime charged with losing the Second Karabakh War in 2020.

The investigation continued along two paths. The first was comprehending how this synthetic oil-eating bacteria was defined, its capabilities and its use; the second was to locate the clandestine testing facility. BL scientists determined that the project was based on the work of Adigozalova, V.A.; Hashimova, U.F.; Polyakova, L.P. and other obscure research studies. Oil-eating bacteria exist in nature, but such candidate strains needed to be genetically modified to prefer naphthenic hydrocarbons.

The first place visited was Yerevan State University, if for no other reason than to identify local petroleum chemists. The notion and motivation was that there must be a formidable body of chemistry and chemical engineering brain trust here comprised of the highly educated Armenian scientists of the Soviet era who were part of the 250,000 Armenians forcibly exiled from Baku during the pogroms circa 1990.

The existing and up-and-coming native Armenian oligarchy, fearing an erosion of their power in all aspects of control over sovereign Armenia, schemed to maintain their hegemony without competition from Baku’s highly educated Armenian class. Not surprisingly, Armenia’s first post-Soviet president Levon Ter-Petrosyan, therefore dumped chemistry as a national academic endeavor. Ter-Petrosyan’s pejoratives referring to Azerbaijani Armenians as Tatar-Mongols or arrogantly insinuating that Karabakh Armenians are not Armenians but instead Caucasian Albanians encouraged discriminatory group thought in the greater society. Such pseudo-academic arrogance was typical of a particular class in the Soviet KGB.

The residual effects of this astoundingly short-sighted view has been evident for thirty years and has been one force of the continuing weakening of Armenia as a sovereign nation. The ‘rehabilitated’ Albans, or Alvans, was a Soviet narrative used to counter the steady increase in Turkic nationalism exhibited by Soviet Azerbaijanis. Ironically, today, Baku also claims that Armenian culture in the Nagorno-Karabakh region is Caucasian Albanian.

The BL team that visited Yerevan State University left almost empty-handed were it not for a middle-aged secretary who heard some of the conversations and spoke to the BL team leader as the group was leaving. She said she knew of a chemist who represented a group of Baku Armenian chemists and technicians. He spent the early 1990s advocating on behalf of this group. His name was Roman Ghambaryan. The secretary said the last she had heard was that Ghambaryan was a taxi driver in Kiev, Ukraine. That must mean ‘old’ Ukraine since after Ukraine’s collapse, losing over two hundred thousand soldiers, Kiev is the capital of the new partitioned rump Ukraine. With Poland having enormous influence in Galicia and Lvov, a substantial population exodus occurred. The debate in BL was whether to locate Ghambaryan and find who remains from his group or contact diaspora Armenian chemists and bacteriologists. Both avenues were pursued.

The BL contacted a new governmental group who was mandated with categorizing and securely vetting Armenia diasporan experts. The previous oligarch-serving unwritten policy—that any diasporan Armenian always is a potential spy—was abandoned and replaced with an evidence-based categorizing procedure. Finding any chemists who worked in the Soviet Azerbaijani hydrocarbon industry was a formidable task as many of these Baku chemists were either deceased, living in one of the eleven time zones in Russia, or living in obscure cities in the United States as part of the accelerated-assimilation refugee admissions package. The active abandonment of non-resident Armenian expertise was a strategic loss for Armenia by purposely eliminating the best and brightest. There would be a time limit set on this search. Time wasn’t a commodity we freely had, especially considering we had not found the testing laboratory for the oil-eating bacteria.

The Prologue

The Western scientists and technicians immediately fled the country as the new, distributed government took jurisdiction in Armenia. Only custodians remained at Armenia’s western-sponsored biolabs. They were of little help as all they did was make sure the air conditioning worked albeit while slowly pilfering and selling all of the lab’s equipment to interested buyers, usually for pennies on the dollar. Ignoring this disheartening pilfering, the investigators moved on to rumored equipment suppliers and even bottled water delivery services at the biolabs. Hopefully they could lead the investigators to the most important objective at hand: discovery of additional biolabs.

BL investigators spoke to a www.menu.am driver who told us that several months earlier, while he was waiting for somebody to come out and pick up an order at biolab3, he was talking with a driver of a refrigerated truck waiting to pick up an insulated container. The menu.am driver remembered this because he has family in Gyumri. The BL investigators knew there was nothing taking place associated with this bacteria at the Gyumri biolab, so perhaps there was another biolab in or near Gyumri. The investigators quickly tracked down the refrigerated delivery service since only a handful of firms offered such capabilities in Armenia. BL investigators spoke with the truck driver. The refrigerated truck went through Gyumri on its way to Bavra, just before the Georgian border. We were told the insulated container would be delivered to a small Soviet-era Zhiguli car waiting at the Bavra border customs post on the M1 highway. No other vehicles were parked at this border post so late at night, yet the car was parked in an odd place. It was later discovered that this place wasn’t that odd and was a known parking area with no video surveillance. This blind spot had been there for years to smuggle contraband between Georgia and Armenia, providing plausible deniability by the authorities. The best the refrigerated truck driver could remember was that the Zhiguli was probably headed toward Georgia, the only logical place to go after arriving there from the south.

Further analysis of the border crossing surveillance video showed that the first Zhiguli to cross the border was at 11:23 pm, over six hours after the insulated container was picked up from biolab3. Investigators spoke with Georgian border officers in Ninotsminda, just over the Georgian border and identified the Zhuguli that crossed the border; a small shop owner at the customs area at Bavra owned it. So where was the Zhiguli in question now? It appeared the Zhiguli was still parked on Armenia’s M1 blind stop — nobody bothered to check that it may have come back from Georgia, or never left Armenia. This entire Zhiguli episode may have been a diversion, as one of the investigators noted — but a diversion from what? The lead investigator called the refrigerated transport firm and asked where the truck went after the claimed drop at Bavra.

The refrigerated truck may have dropped off the insulated container elsewhere. The truck never returned to headquarters until later the next day. It was standard procedure to allow drivers to take trucks home, sleep and return to work the following day. The truck driver admitted to this. However, in this case, the truck arrived several hours late. The investigators asked for the truck’s kilometer reading when it returned to the firm’s dispatching building the next day. Based on the kilometer reading, the truck could only have traveled to a finite number of places. This truck must be the one in question since the time and distance matched driving to Bavra and back. The truck driver claimed to have delivered the small insulated container to the Zhiguli. He was instructed to place the container in the Zhiguli’s trunk, which was not locked. What happened at the Georgian border?

We requested the Georgian border officials to provide us with any videos of vehicles on the day in question heading north on the Georgian section of the Armenian M1 highway. There was no immediate response, so we visited the Georgian border security administration and viewed video surveillance of all the Georgian road traffic immediately past the Armenian border. We noticed a small Toyota Prius seemingly coming from nowhere on this road. It may not have come across the Armenian border, but instead had always been in Georgia. We followed the intermittent surveillance of the Prius until about a kilometer from the Georgian section of the BTC pipeline, just south of Rustavi, many kilometers to the east. We suspected something would happen at this pipeline, even though there was near-continuous aerial reconnaissance along its entire length, from Baku to the Turkish coast. Less than half an hour later, the driver or other people in the car returned to the Prius and headed toward Tbilisi. Surveillance was lost in the city’s neighborhood back streets. The following morning, the same Prius was seen proceeding through Armenian customs at the easternmost border station at Baghatashen with only a tiny piece of luggage and a new laptop bag. Neither the Georgian nor Armenian border guards inspected the contents of either item, as shown on video.

Although we had plenty of evidence, car types, license plates, and a picture of the Prius driver from the surveillance video, finding the car and its driver would take a while. However, the car was relatively easy to find with a Georgian license plate. It was parked at a local Armenian IT company near the ‘Engineering City’ but still inside the Armenian capital, Yerevan. Investigators entered the offices and found the driver. The driver was a Georgian who was giving a software product presentation. The investigators waited until he was finished and spoke with him in an empty office. The Georgian had no idea what the investigators were asking. He appeared to be a classic computer geek. The Georgian was then taken to an undisclosed facility and questioned further. It turns out the Georgian was innocent but may have been tricked into being a mule of some type. He told us his car appeared to have been stolen the previous evening, and either he forgot where he parked it, or it was stolen and returned. The police were going to arrest him for making a false claim. The investigators found his missing laptop bag on top of the spare tire and methodically tore apart the Prius and the guy’s luggage and then examined his laptop. In the old laptop bag there was a small compartment with a jammed zipper. The zipper was eventually opened, and a small amount of dirt was found in a fold. It was the only dirt in an otherwise clean case. The dirt appeared oily. The dirt was tested at a local lab, and it was shown to contain crude oil. Is it possible this crude was somehow associated with the BTC pipeline? When this find was reported to the Georgian authorities, they finally offered their complete assistance. The BL could not tell them what was transpiring at the biolab raids.

The Georgians did their investigation, reported a bizarre story to us, and verified what the Georgian IT guys told us. The owner of this Prius, the Georgian IT person, said the car was ‘missing’ at night, but then he found it back in its parking space in the morning. The Georgian police were going to charge the IT person with a false police report. The owner said that when he initially parked his car, he took his laptop out and left the bag in the car. When the car magically reappeared, his laptop bag was missing. The Prius owner was perplexed and thought it was ‘one of those days’ when he felt he had lost his car and laptop bag. It was suggested that the Prius was temporarily stolen. If the laptop bag was used to transport a sample of Azerbaijani crude oil, what did the refrigerated truck have to do with this? It was postulated that the refrigerated truck must have left something that required refrigeration somewhere near the Armenian-Georgian border. The thieves must have then placed the laptop bag in the trunk of the Prius containing the bacteria incubator atop the spare tire. In Yerevan, another team broke into the trunk, took the bacteria incubator, and left the laptop bag where the perplexed owner would eventually find it.

More information was discovered as more pages from naphthenic_hydrocarbons.docx were decrypted. It was soon determined that every page had its own encryption key. One piece of information that BL’s biochemists discovered was that the naphthene-eating bacteria had to be introduced into the oil when the oil was at a specific temperature range. However, that temperature had to be empirically measured. Perhaps the dirt and oil were due to having gathered dripping oil from the BTC pipeline near Rustavi. Maybe the cool, insulated container fell or was placed in the ground under the BTC pipe, and contaminated dirt entered the laptop bag. The Georgian police in Tbilisi didn’t inspect the Prius when it mysteriously reappeared. Investigators believed that the Georgian’s car was broken into while in Yerevan, and whatever was in his laptop was removed.

Unfortunately Roman Ghambaryan, who might have been the person to consult on this matter, appeared to be deceased. He would have been the best person available to locate those who might have been able to address some critical issues BL’s biochemists had. Thus the BL team’s only remaining option was to locate vetted diasporan biochemists with bacteriology and petroleum chemistry expertise. BL found a biochemist who worked at a bio-weapons facility about 140 kilometers south of Salt Lake City, in the US state of Utah. There was little time to navigate all the bureaucracy required to arrange for this person to come to Armenia. The BL knew what they wanted to discuss with this biochemist, although the BL felt constrained knowing he had a US security clearance that was a click above Top Secret.

The BL spoke with this person over a Zoom call since his clearance didn’t allow him to have an encrypted semi-private messaging account like Signal Private Messenger. On the Zoom call, we asked him why an oil-ingesting bacteria might be introduced into a target while cool. He said that one would need to measure bacteria growth and ingestion of nutrients as a function of both time and temperature, meaning whatever was in the laptop bag was a portable bacteria reactor with data-logging capability. Accurate data will be lost if the process proceeds too rapidly, so the temperature must rise slowly. The conclusion was that this oil-digesting covert operation needed the data for something. The biochemist said that the temperature at which the bacteria multiply optimally could be obtained in one slow temperature-increasing growth cycle. The procedure must be restarted on a new sample if not done correctly. BL concluded that some operation was being planned real soon and they needed to find out what it was and who was running it. In any case, it was hypothesized that the bacteria at a low temperature had to be introduced into the crude oil sample; and as it warmed, the bacteria count could be measured by the amount of carbon dioxide released as a byproduct. With this data, the optimal temperature for the shortest bacterial doubling time for the bacterial colony could be established.

An item the Georgians missed in their investigation of the contaminated dirt site at Rustavi was what appeared to be thin tire tracks, such as those of a bicycle or an electric scooter. We saw this in the video files. The tracks appeared intermittent and could have been easily overlooked. We asked the Georgian BTC security to grant us an on-site inspection of the pipeline site where the Prius or its driver was suspected of going. A couple of BL investigators went in two directions along the pipeline (looking innocent), but we were only interested in the westerly direction. The tracks were well washed out by rain and foot traffic, but the BL investigators knew the tracks of interest led in the westerly direction. A BL investigator noticed an inspection port atop the center of a pipeline section that looked a little taller than the others and had fresh fingerprints on it. He kept this to himself as the team returned to their four-wheel drive vehicles. On the way back to their vehicle, the sharp-eyed inspector told the others of the irregular inspection port. The group then immediately took scores of long-distance photos of the inspection port (and other places on the ground and in the easterly direction as a diversion) as the Armenian team didn’t want to alert the Georgians. To ensure the BL group had some plausible deniability, we asked the Georgians to recheck the pipeline when they had time to see if anything looked out of place. The teams requested this while noticing the Georgians were irritated at the Armenians for apparently wasting their time. Even though the Georgians spoke Russian and English with the Armenians, they spoke Georgian among themselves. We had an Armenian born in Tbilisi with us, so we knew what they were discussing. Back in Yerevan, our research showed that all the inspection ports on the Rustavi sections and much of the pipeline in Azerbaijan and Georgia had identical inspection ports. What was going on with the taller port?

The BL teams were among the best and brightest in Armenia. They were trained in many topics, had relatively high IQs, and were critical thinkers. For this reason, they assumed that their vehicle was probably subject to long-distance laser or microwave vibration sensing. They were careful what they spoke, using unique hand gestures below the window line. Learning such hand signals was part of BL’s training. They had already auto-scanned their car for hidden bugs and found none. On their way back over the Armenian border, they immediately changed vehicles. A serious discussion took place in the new vehicle. The vehicle was a Faraday cage with electrically conducting window glass.

It was strongly suggested that the slightly taller port contained a dormant colony of bacteria that would devour crude oil with a high concentration of naphthalene. However, at that point, it was unclear to any on the BL team if there was enough naphthalene in Caspian Sea crude for the bacteria to reach a critical doubling time. The Naftalan oil wells were several hundred kilometers from Azerbaijan’s Caspian wells. Perhaps there was enough naphthalene in Caspian crude for the bacteria to sustain itself and turn the crude into water, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and liquid junk.

Back in Yerevan, the BL Directorate surmised that a bacterial attack would occur on Azerbaijani oil and that they had enough actionable data. They heavily discussed what to do about this situation. The BL knew they must keep this knowledge from the rest of the government for many reasons. Even though Armenia finally earned international respect for not only strengthening its sovereignty through its new distributed government and forcing many scoundrels from Armenia and Azerbaijan, it still had to protect itself from internal enemies. The BL decided to wait and see if the bacteria would do its job in decimating Caspian oil. Their silence would provide a level of plausible deniability.

But the BL leaders needed to know what was planted in the tall inspection port. A secret BL team returned to the site of the tall inspection port. The goal was to verify what was in the inspection port and replace as many existing components as possible with Georgian- and Russian-made ones into the mechanism. The team could only replace a few parts and had to do this at lightning speed as it was still unknown when or who would release the bacteria. The engineers concluded there were three methods initiating the injection of the bacterial colony, (1) a timer, (2) a temperature sensor, and (3) a remote control mechanism. Any one of these could unleash the bacteria into the pipeline. The BL Directorate concluded that disrupting Caspian oil would be in the interest of Armenia on several levels. After all, the unrepentant West blew up the Nordstream gas pipelines from Russia to Germany, and eating Caspian oil followed what was considered a successful ‘diplomatic’ mission. And an Azerbaijan without oil or natural gas would no longer be an asset or a nation that could attack Armenia with impunity. Without fossil fuel, the West would no longer have a reason to turn a blind eye to Azerbaijan’s genocidal campaign against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh.

The Bacteria are Released

After several days of waiting and hoping for something to happen, it was reported that in hundreds of locations in both Georgia and Turkey, significant sections of the BTC line exploded, and an enormous ecological disaster was unfolding. Of the many byproducts of oil-digesting bacteria, the most devastating included carbon dioxide gas and water, the increasing pressure of which ruptured the BTC pipeline. Both byproducts caused over spinning of pipeline pumps which caught fire, burning crude oil along a path from southern Georgia to the Turkish Mediterranean coast. The bacteria was slowly approaching Baku, and even though this was opposite the direction of oil flow, enough of the pumps had failed, leaving stagnant oil to be devoured by the bacteria.

Eventually, the bacteria spread to the Russian Black Sea oil port at Novorossiysk and the Supsa line on the Georgian Black Sea coast. The oil wells in Naftalan, Azerbaijan, are now empty; what was crude oil is a thick white foam, and the hydrogen sulfide gas made hundreds of square kilometers of Azerbaijan smell like rotten eggs. The entire BTC hydrocarbon pipeline is in ruins. British Petroleum’s (BP) stock has plunged. Rumors persist of short selling of BP stock, netting billions of dollars. Somebody knew this disaster was coming, like the short-selling of airline stocks days before the 911 events in New York.

This disaster surpassed the destruction in February 2023’s Turkish earthquake by orders of magnitude. The US military removed all their B61 hydrogen bombs from Turkish territory easing Turkey’s demotion from NATO.

No experimental test site that was ever located was associated with this synthetic bacteria. It was concluded that the refrigerated truck, Toyota Prius, and a laptop bag were the final test platforms. Azerbaijan and the UK are furious at Georgia and Russia as they were ‘somehow’ connected with the bacterial destruction of the BTC line. Armenia offered assistance to Georgia in tracking down the guilty. The BL destroyed any evidence as to their involvement. All that remains is this account.

No experimental test site that was ever located was associated with this synthetic bacteria. It was concluded that the refrigerated truck, Toyota Prius, and a laptop bag were the final test platforms. Azerbaijan and the UK are furious at Georgia and Russia as they were ‘somehow’ connected with the bacterial destruction of the BTC line. Armenia offered assistance to Georgia in tracking down the guilty. The BL destroyed any evidence as to their involvement. All that remains is this account.

Destruction in Naftalan, Azerbaijan

A couple of months passed, and the Aliyev family dynasty of Azerbaijan finally fell. There are battles between militias of financially depleted oligarchs on the streets of all major cities in Azerbaijan. A grave embarrassment to the BL was that it never determined who planned this operation or how the insulated container on the refrigerated truck ended up at the Georgian section of the BTC pipeline. The former mattered; the latter was a fait accompli.

Postscript

The leader of BL’s investigation team received an old-fashioned handwritten letter containing a single-page montage of several images (see Page sent by Ghambarian, with redactions by the BL team) from the naphthenic_hydrocarbons.docx file. The envelope was signed in Russian, Роман Гамбарян — Roman Ghambaryan!

Author: David Davidian (Lecturer at the American University of Armenia. He has spent over a decade in technical intelligence analysis at major high technology firms. He resides in Yerevan, Armenia). A collection of his work can be seen at shadowdiplomat.com