The digital economy, driven by technological innovation and digital transformation, not only plays a key role in international trade, but also directly influences geopolitical relations between countries.

To protect their national enterprises, key infrastructure, data resources, etc., countries have introduced consequent policies, resulting in a complex political and economic game. The development of the digital economy has transformed from a mere commercial issue to a national security risk, playing a key role even to competition and cooperation between superpowers.

Among the world’s three largest economies, Europe’s digital economic development is relatively slow, compared to that of the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China. To consolidate its competitiveness and influence, the European Union has recently proposed a series of digital policies and draft laws, both to actively defend sovereignty in this area and to try to change the status quo, through three main strategies: containment, reorganization and disruption.

The first is “containment,” which involves setting rules for the European single market, while also attempting to slow down the scale of development in the United States of America. Since taking office, Commission Chair Ursula von der Leyen has introduced a series of bills in the digital field, such as the Digital Markets Act, the Digital Services Act, and theAIAct.

On the surface, these bills appear to be aimed at protecting the rights and interests of European citizens. However, judging from the published regulatory list, most of the EU’s proposed laws in the digital field are aimed at U.S. tech giants, particularly digital platforms.

From a deeper geopolitical perspective, the United States of America has always been Europe’s main commercial competitor. In important technology sectors, the European Union is trying to trigger a “Brussels effect” (when we talk about the “Brussels effect” we refer to the European Union’s ability to unilaterally regulate global markets) by setting strict standards and market access rules to influence U.S. progress in digital technology development.

The second is “restructuring,” which aims to influence the debate on international standards through digital trade agreements and by reconfiguring the global supply chain.

The European Union has realized that it is not enough to slow down international development by merely setting market access standards. The EU’s long-term goal is to create an independent supply chain, but this requires not only time but also strategic international cooperation.

For this reason, the EU is working with international partners through a series of digital trade tools to try to identify the EU’s strengths and weaknesses in the global value chain in order to fill the gaps. Recent concrete manifestations are the US-EU Trade and Technology Committee (TTC) established by the European Union and the United States of America and theDigital Partnership Agreement (DPA ) signed with Japan, the Republic of Korea (South) and Singapore.

Although Europe and the United States of America have long competed in business, they have formed a strategic alliance on international security issues. In this context, the TTC established by the United States and Europe focuses on the joint development of emerging future-oriented technology standards, including reliable AI and 6G technologies.

The goal is to strengthen the leadership position of Europe and the United States of America in science, technology and industry worldwide. Moreover, considering the complex supply chain of the global digital industry, especially the semiconductor industry, the European Union clearly sees it as a key development area.

Asia plays an important role in this field, so the European Union actively signs DPAs with Asian countries. While DPAs have no legal effect and no financial commitment, they help the European Union create a network of supply chain cooperation in Asia, with semiconductors at the center, and expand into areas such as infrastructure and data sharing for future-oriented technologies. The long-term goal is to rebuild the global industrial supply chain and ensure its advantage in future technology competition.

The third is “revolutionary,” focusing on reducing the digital divide between member states, integrating resources and creating an interconnected single market.

For the European Union, one of the important goals of controlling digital sovereignty is to build an independent supply chain to bring a product or service to market, transferring it from supplier to customer (supply chain).

At present, the European Union’s biggest dilemma is that the digital divide among its member states is too wide, and it is difficult for the European Union to integrate the strength of its 27 member states (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Spain, Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia and Sweden) to compete with the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China.

For this reason, in September 2021, the European Commission proposed the “Digital Decade 2030,” which became the first digital development program approved by the European Commission, the European Parliament and the European Council.

The plan’s “digital compass” serves as an assessment tool and covers four dimensions: digital skills, digital infrastructure, digital business transformation, and digital public services.

The indicator approach reflects the fact that the European Union hopes to reduce the differences between member states in terms of digital skills and digital public services. For example, by 2030, 80 percent of citizens will have basic digital skills and 100 percent of citizens will have digital identities.

The European Union aims to align levels of digital skills and digital governance among member states and to establish interconnection standards within Europe. However, in developing emerging industries and technologies, the European Union allows member states to have heterogeneity and develop their own industries of greatest national advantage based on their regional industrial characteristics. At the same time, it encourages member states to propose multinational plans and jointly develop large-scale projects that a single country cannot develop independently, so as to achieve economies of scale.

Through this set of strategies and policies, the European Union is demonstrating its ambitions in the digital economy. This not only highlights that the digital economy has become a key factor in geopolitics that cannot be disregarded, but also shows that in the future, competition and cooperation among countries will define the new landscape of the global economy and influence the direction and shape of international trade.

Judging from the European Union’s recent actions, influencing and guiding international technology standards and market regulations will be an important way for the Union to safeguard its digital sovereignty.

However, in the face of global protectionism and digital sovereignty strategies, Europe, the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China could use their demographic advantages to diverge on digital standards, forming a world with three or even four sets of standards (plus India).

Therefore, businesses, in addition to mentally preparing for higher compliance costs, also need to think about how to build an independent supply chain in a complex geopolitics, capable of facing geopolitical and economic wars at any time; governments, on the other hand, need to think about how to help businesses align with international standards and regulations to promote business resilience.

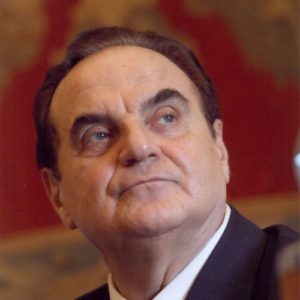

Author: Giancarlo Elia Valori – Honorable de l’Académie des Sciences de l’Institut de France, Honorary Professor at the Peking University.

(The views expressed in this article belong only to the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of World Geostrategic Insights).