By Fyodor Dmitrenko

Recently, before the last autumn leaves had fallen, an interesting chain of events kicked off in Paris. Between the 4th and 5th of November, Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev visited the Elysee palace to meet French President Macron.

Coming on the anniversary of Macron’s visit to Astana in the previous year, the meeting – partially detailed in an official joint declaration by the two leaders – dealt with a number of issues including but not limited to supporting the signing of a peace treaty between Armenia and Azerbaijan along the lines of the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1991, supporting joint cooperation to deal with climate change e.g., in the upcoming One Water Summit in Riyadh, and welcoming the exhibition “Kazakhstan treasures of the great steppe” at the Musee Guimet.

This in itself is quite interesting – as it is difficult to imagine a major world leader travelling almost 6,000 km to exchange diplomatic niceties, however what makes this story genuinely noteworthy is the fact that just 2 days after Tokayev’s return to Astana (on November 7th), Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov met with the president in a discussion behind closed doors that has now led to the definitive confirmation of a prior pledge made in July of a visit on the 27th of November of Russian president Vladimir Putin.

This of course begs the question – why did the initial meeting take place, and what was so important that Macron and Tokayev meeting drew the attention of the Kremlin?

Reasons for the Macron-Tokayev meeting: France

While there could certainly be a multitude of reasons for this meeting, the most likely one is Uranium 235.

First some context – France has a long history with nuclear energy given that they were arguably the first to discover it (with Antoine-Henri Becquerel first investigating radioactivity in 1896, followed not far behind by Marie Curie and her husband) opening the field to many other international scientists, with the project of civilian nuclear power being first institutionalised in France by President Charles De Gaulle with the creation of the Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique or CEA in 1945.

However it was not until the 1970s that nuclear power really took off in France due to the high oil prices following the Yom Kippur war driving France to switch to nuclear energy according to a report published by the French embassy in Washington in 2013.

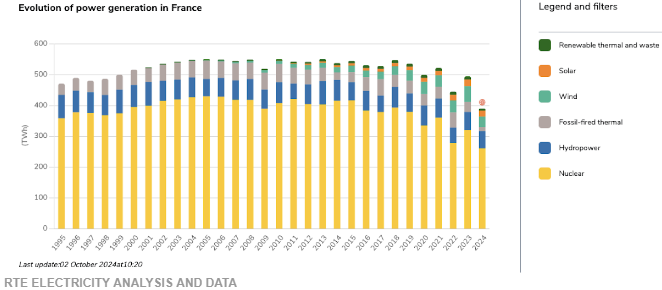

In the present day France is still extremely reliant on nuclear energy with the latter comprising around 65% of French electricity generation in 2024 according to France’s Electricity Transmission Network (RTE) – a subsidiary of the EDF (Électricité de France) – France’s state-run electricity company.

While this has made France a major leader in the nuclear energy field, and helped mitigate supply issues affecting other European countries e.g., Germany, resulting from the loss of cheap gas following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, it has also made France vulnerable to supply fluctuations of their own.

This issue came to the forefront in July 2023, when incumbent Nigerien president Mohamed Bazoum, who had maintained cordial relations with France through cooperation in various fields e.g., supporting the French fight against Jihadism in the Sahel by allowing them to base their 1,000-1,500 troops in Niamey, was violently overthrown by the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (CNSP), which set up a military junta that called for an end to French presence, drawing most of their legitimacy through claiming to resist French neo-colonialism – rhetoric that they have backed with actions like revoking 5 military agreements forged between 1977 and 2020 and beginning discussions to stop using the West African CFA Franc.

This was a concerning development for France who derived almost 20% of their uranium imports from the country in 2022 according to Le Monde, with Orano (a majority state owned nuclear firm) operating 2 mines – one at Imouraren where Orano held a 63.52% stake, and one at Aïr run by SOMAÏR – a company 63.4% owned by Orano (with a third run by COMINAK – another Orano subsidiary – being depleted in 2021).

Shortly after the coup Orano would be forced to stop operations at the Imouraren site due to the withdrawal of the operating licence by the Nigerien junta in June 20, 2024, with the company recently choosing to further cease operations at Aïr as well effectively stopping all remaining uranium production in Niger from October 31st of 2024 citing “financial difficulties” stemming from the closure of the main supply and export corridor by the Nigerien authorities. These collective developments have forced France to look for partners that could cover this uranium deficit without having to make the expensive switch to other energy sources – which brought it to court Kazakhstan.

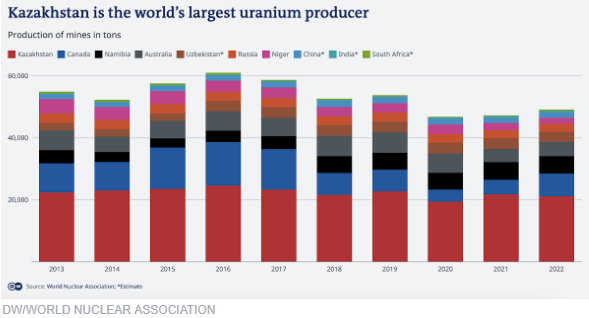

This decision is not surprising given that Kazakhstani company Kazatomprom is the single largest producer of uranium in the world with a market share of approximately 23% at 11,373 tonnes extracted in 2022 on an attributable basis (i.e. excluding joint ventures), almost double the production of Canadian firm Cameco – the next largest uranium supplier at 12% of market share and 5675 tonnes of uranium extracted in the same year according to the World Nuclear Association. Furthermore, Kazakhstan was already France’s largest uranium supplier at 37.3% of the 7,131 tons of uranium France imported in 2022 according to Le Monde, so the step built on a significant prior precedent.

Reasons for the Macron-Tokayev meeting: Kazakhstan

While less desperate, Kazakhstan on its part also has good reasons to want to improve ties with France. The most obvious of these is the economic benefit derived from selling France more uranium with Kazatomprom which sold France $193,375.22 thousand worth of uranium in 2023 according to WITS being majority owned by the Kazakh state (with approximately 63% of shares owned by the Samruk-Kazyna Sovereign Wealth fund and a further 12% by the Ministry of Finance, leaving only around 25% in private hands), so any new trade deals with France directly fill the state’s coffers, allowing greater economic growth.

Nor is the bilateral economic relationship limited to uranium alone, with Tokayev claiming that bilateral trade amounted to around $4.2 billion in 2023 with French companies like Total energies and Alstom among many others having further injected an approximate total of $19.5 billion in FDI into the Kazakh economy according to the Times of Central Asia.

On the other hand, a perhaps less obvious reason that Kazakhstan may be seeking to improve bilateral ties could be an attempt to diversify the influence exerted upon it by its current partners. Kazakhstan’s geopolitical ties have long been with Russia as evidenced by Russian still being more widely spoken (83.7%) than Qazaq (80.1%) according to the CIA world factbook, from its colonisation by the Russian empire in 1868, and the formation of the Kazakh SSR in 1925 through to the collapse of the Soviet union in 1991.

This influence is most obvious through the presidency of Nursultan Nazarbayev, who has ruled the country since at least 1989 when he was appointed First Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan (while also holding several positions in government including prime minister in 1984). Under Nazarbayev Kazakhstan was a founding or otherwise key member in a number of Russian dominated regional organisations including the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) which is a security organisation reminiscent of NATO formed in 2002, and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) single market union formed in 2014.

Beyond political influence a significant portion of Kazakh business elites have also historically oriented themselves towards Russia due to the aforementioned socio-political ties, but more importantly because of infrastructure – with 80% of Kazakhstan’s crude petroleum according to Le Monde passing through the Russian Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), a number that has seen little change despite attempts in 2022 to carry more over the multinational Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline due to the latter’s limited capacity.

However since Nazarbayev has nominally resigned due to significant domestic pressure in his 4th term in March 2019, his chosen replacement Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has appeared to have begun a gradual move out of the Russian orbit through the increasing influence of new partners – most prominently China and France.

Having focused his education on understanding China (graduating from the Moscow State Institute of International Relations) and having begun his state career as a diplomat to Singapore and the PRC in 1975-1979 and 1985-1991 respectively, a key element of Tokayev’s foreign policy has so far been a streak of Sinophilia, in stark contrast to his mentor’s emphasis on relations with Russia, while maintaining positive relations with a third country outside the dichotomy of Russia and the PRC to avoid being subsumed by one of the prior powers – France.

It is important to emphasise however that the development of ties between Kazakhstan and France does not signify a Kazakh attempt at democratisation or a resolute turn to the West with Tokayev seeing no issue in turning to Russia when it suits his interests, as demonstrated by his request for 2,000 CSTO soldiers to deal with civil unrest in 2022. Instead the nurturing of a partnership with France appears to be aimed at increasing Kazakhstan’s leverage in relations with its traditional partners, thereby providing it a greater degree of independence in their foreign relations.

Moscow’s response: Concerns and Countermeasures

Given the increasing closeness between Kazakhstan and France, why then have the former’s traditional partners not attempted to stop this development?

The short answer is by all accounts Russia appears to be trying to stop it right now.

On November 7th, 2 days after Tokayev’s return to Astana the president received a visit from Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. While the meeting itself was scheduled and followed standard diplomatic protocols – a few details stood out. First of all the timing – just after Tokayev’s return from France – was noteworthy. Secondly, TASS reported a “lengthy” closed-door discussion between Tokayev and Lavrov – somewhat unusual given the difference in diplomatic ranks and the fact the only concrete announcement that officially came out of it was the confirmation of Putin’s visit which had already been hinted at in July of this year, in contrast to the lengthy joint declaration between Macron and Tokayev earlier in the week. While each of these elements taken separately – the timing after the Paris visit, the extended format of discussions with few returns, and the announcement of Putin’s visit – might be coincidental when viewed separately, together suggests a level of urgency in Moscow’s diplomatic response that goes beyond routine bilateral relations.

A key reason for this reaction could be the high state of tension (or even arguably pseudo war) between Macron and Putin over the war in Ukraine with the former firmly supporting the Ukrainian forces with a cumulative total of almost €4 billion of military aid (€1.7 billion in 2022 and €2.1 billion in 2023) and training of Ukrainian troops like that of the ‘Anne of Kyiv’ brigade. Furthermore, Macron has been one of the main advocates for EU re-armament – a clear threat to a Kremlin strained by war, a process that Macron has sought to accelerate with him stating rather fatalistically “If we decide to remain herbivores, then the carnivores will win” in a press conference following the election of Donald Trump who has made lessening US continental commitments a prominent part of his re-election campaign.

Another possible reason that Russia may be so perturbed by the growing relationship between France and Kazakhstan is the inverse of why Kazakhstan is so interested in developing it in the first place – the potential loss of its influence in central Asia. Since the fall of the Soviet Union between 1989 and 1991 which in a 2005 speech President Putin has famously termed the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century,” Russia was largely beset by crises of influence in a similar manner as those experienced by the former colonial powers of Britain and France following WW2. The most famous examples of this trend are of course the Eastern European former-Warsaw pact nations e.g., the GDR, Poland, Romania, Hungary, and the Baltic states choosing to join western aligned organisations like NATO or the EU. However, despite the lesser coverage in Western news media, this trend also took place (if in a more muted form) in central Asia, with new players challenging Russia’s monopoly over geopolitical influence in the region – most prominently China.

For this reason even if the cooperation between France and Kazakhstan has remained (and likely will remain) limited, Russia may attempt to stop its furthering regardless because while it cannot stop Kazakhstan associating with China, due to Putin’s increasing reliance on the latter, following the loss of European markets for most Russian exports, it can absolutely attempt to stop this development with France.

Conclusion

Whether France’s diplomatic foray into Central Asia will gain it the energy security and influence it so desires, or whether Russia will cut this budding partnership off before it has a proper chance to blossom, is still up in the wind. However there is little doubt that the eyes of all the concerned parties will be on the upcoming Putin Tokayev meeting as it could not only determine the answer to this question, but also the strategic trajectory of Kazakhstan, and perhaps even that of the Central Asian region as a whole.

Author: Fyodor Dmitrenko – Student at Sciences Po Paris, currently enrolled at the Asia-Pacific campus in Le Havre. Fyodor’s analysis interests encompass a wide range of topics, including energy, macroeconomics, and security, to better understand the changing global order, with a focus on the middle powers of Central Asia and the Balkans.

(The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of World Geostrategic Insights).

Image Credit: AFP