By Nahal Sheikh

China has been a very active player in South Asian development projects, specifically trade route developments. Although such investments by China are historical, the degree of their presence at this moment is unmatchable.

The on-going project is called, the ‘Belt & Road Initiative’ whose aim is to build up China’s global trade network. Began in 2013 by Chinese president Xi Jinping, the project is estimated to invest about one trillion dollars in trade programs across sixty-eight countries.

China’s ‘Belt & Road’ expansion in South Asia

China is investing large amounts of capital in countries such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Nepal for the trade initiatives. What is significant to keep in mind is that these very countries are most probably unable to pay China back. For example, China funded the construction of a Sri Lankan sea port, Hambantota. Unable to pay back, Sri Lanka ended up with a deal with China of giving away the port to them on a 99-year lease. This way, China secured a port that is very geographically strategic for a global trade route. This form of loan is called ‘Debt-Trap Diplomacy’: a type of diplomacy based on debt where the debtor or small states are eventually forced to abide by external economic and political dictations as a form of “re-payment”.

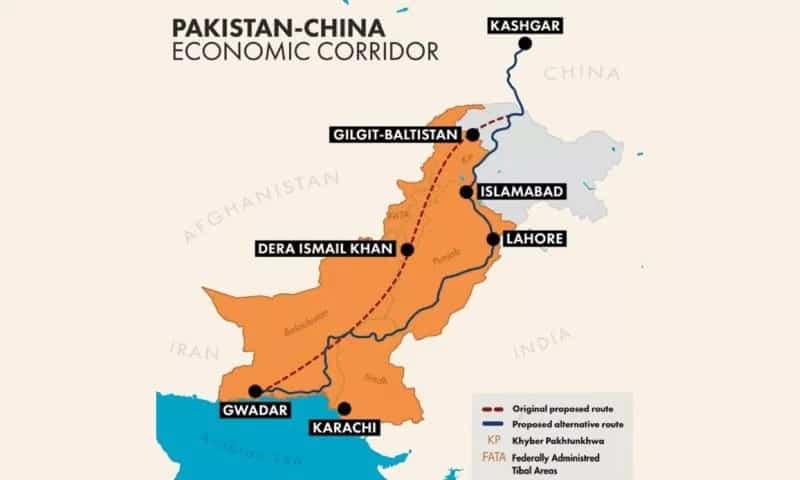

Similar scenarios are building up in Pakistan under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a project worth approximately 62 billion dollars – the biggest Belt & Road project. Here, Pakistan’s infrastructure is being built on a grand scale covering areas spanning from the North to Southern provinces. The infrastructure includes highways, railroads, ports, and pipelines. Some of the major projects are the Gwadar Port, Karachi Circular Railway, and the Karakorum Highway. Their construction means an easier and more efficient access to the Indian Ocean. However, the project is drowning Pakistan in excessive debt. It is estimated that by 2024, Pakistan will owe China around 100 bn dollars. When asked Chinese officials about these concerns, the answer revolved around how these loans are on concessional basis, which means they will be specially subsidized by the Chinese government. Hence, they will not act as a “burden” to Pakistani economy.

Is the U.S. threatened?

However, analysts believe Pakistan will end up asking for a bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) of about 8-12 bn dollars. The issue, aside from the fact that Pakistan will be in immense debt, is that the U.S. is quite worried about providing the bailout – being the major IMF contributor. U.S. simply does not want its money helping Pakistan pay off debt to China. At the same time, refusing to pay the bailout does not sound like a smart decision either since the IMF’s role is to help developing countries progress. Which Pakistan technically will through CPEC. More importantly, not helping Pakistan could cost U.S. a close ally and de-stabilize their position in South Asia. Thus, by helping, U.S. could aim to mitigate Chinese influence in Pakistan and gain grounds for its control. For example, it could put conditions on Pakistan borrowing further from China.

Pakistan’s strategic spot

On one hand, it will probably need a financial helping hand from the IMF, mainly U.S. Simultaneously, the country is in dire need of all the infrastructure development stemming from the Belt & Road projects. As a result, either the U.S. could show dominance again in the country and region by minimizing Chinese control. Or, China could ‘win’ and increase its expansion policies, replacing the U.S. as the centre of global trade. So far, Pakistan seems like a vital yet passive actor in this global play, gradually trying its best to economically foster by any means possible. In another reality, Pakistan may just come out on top and end up dictating whether the U.S. or China will be the next superpower.

The reality behind China-U.S. trade war

The China-U.S. trade dispute represents the current power ethos where U.S. power has been declining globally over the past years. Given this opportunity, China is growing economically in expanding its influence to areas that are highly strategic to the future economy of the world. Although the U.S. still has the largest GDP produced globally, China is surely catching up. For instance, since 2013, China passed the U.S. as the largest exporter of goods and services in the world. In addition, if we look at past comparable records, in 1970 the U.S. contributed 21.2% of total global economic output. Until 2000, this remained consistent after which it has declined each year. By 2025, it is expected to decline till 14.9%. In contrast, China was responsible for only 4.1% of total global economic output in 1970. It rose to 15.6% in 2015, and is expected to rise till till 17.2% in 2025.

More importantly, the Chinese approach to ‘modernized’ expansion does not limit itself to traditional military-security aid and development, but rather on economics. It calls for a grand connection of South Asian countries – that subject to decades of fragile development – are now foreseeing a possible unified financial progression. As such, the Chinese stance is one of deep interdependence. This is a serious geopolitical transformation led by Chinese prowess that clearly acts as a threat to the U.S. In the upcoming years, China’s rise will be fascinating to observe in the light of how the U.S. reacts to it, especially its reaction to the South Asian Belt & Road initiative.

(The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of World Geostrategic Insights).